Online Meta-Learning (Follow the Meta-Leader)

10 August 2020

Modern deep learning methods have gotten extremely good at learning narrow tasks from large troves of data - but each model is often a one-trick pony. Models often need huge amounts of data, struggle to extrapolate from one task to another, and can experience catastrophic forgetting (melodramatic much?) when they have to learn new tasks. Is it possible that a single approach could help solve all three problems at once?

Authors

- Chelsea Finn (Assist. Prof., Stanford - IRIS)

- Aravind Rajeswaran (PhD Candidate, UWash - ADSI?)

- Sham Kakade (Prof, UWash - ADSI?)

- Julian Togelius (Assist. Prof., Berkeley - BAIR)

ArXiV: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1902.08438.pdf

Background

Meta-learning (or ‘learning to learn’) has been a subject of recent interest. People have generally grown to accept deep learning’s ability to hone its skills on single tasks, but most real-world applications do not have huge treasure-troves of data. In the real-world, we have to extrapolate from information we learned about similar tasks in order to solve new tasks - we can’t just try the new tasks thousands of times.

Similarly, if you were to forget your old tasks every time you learned a new task, you would spend your whole life trying to relearn things you’ve already done. Nonetheless, this problem is very prominent in deep learning. If you change the loss function of your network from one task to another, it will train to minimize the loss on that new function without regard to preserving the performance on the old task. This problem of devising a model that can continuously learn new tasks (and remember old ones) is known as life-long/online/continual learning.

Core Idea

This paper builds VERY heavily off of a previous paper that two of the authors (Finn & Levine) wrote - Model-Agnostic Meta-Learning (MAML). For a quick recap given a set of tasks \(\mathcal{T}\) that are sampled with some distribution, the goal is to find some set of weights \(w\) that minimize the loss after a finite number of gradient descent steps, averaged over all of the tasks in \(\mathcal{T}\). In other words, we want to find good starting weights from which we can learn all of the tasks quickly. In this paper, the authors consider the version with just one gradient descent step :

\[L(w) \propto \sum_{t \in \mathcal{T}} L_t(w - \alpha \nabla L_t(w))\]Where \(w\) are the meta-weights, \(L_t\) is the loss function for task \(t\). MAML basically tries to find $w$ to minimize \(L\), which is just the average loss after one step of gradient descent. This paper makes a (very small twist) - because we’re seeing the tasks one at a time, instead of minimizing the expectation, we just minimize the value over the tasks we’ve already seen.

Details

If we order \(\mathcal{T}\) so that we see the tasks one at a time, the traditional goal would be to minimize our regret:

\[R(w) = \sum_{i=1}^{|\mathcal{T}|} L_{t_i}(w_i) - L_{t_i}(w^*)\]where \(w_i\) are our parameters after seeing the first \(i-1\) tasks, \(L_{t_i}\) is the loss associated with the \(i^{th}\) task in the sequence and \(w^* = argmin \ R(w)\).

In English, our regret is the total loss that we accrued minus the loss that we would have accrued if we had done everything perfectly.

The algorithm that attempts to directly minimize this objective is called follow the leader (FTL) for some reason.

The authors suggest optimizing a slightly different objective - what if we let ourselves learn a little bit on each task before being evaluated?

They provide the following motivating example:

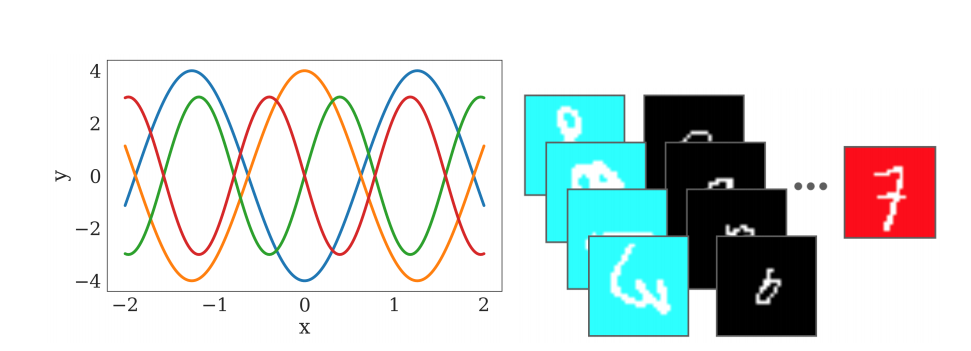

It will probably be easier to learn one sine wave after you learn 3 others...

A single algorithm trying to learn all of the sine waves on the left would probably fail, but there is definitely information to be gained by remembering the properties of sine waves you learned from the others.

Similarly, on the right, an algorithm might reasonably assume that all red images are sevens, but if it sees that it’s just being trained in batches and each batch has a different color, it can safely ignore it.

As a result, the authors propose to slightly change the objective:

where \(U_i\) lets us do a little bit of learning on the dataset before we’re evaluated. The authors dub this algorithm ‘Follow the Meta-Leader’ (FTML). As I’m sure you can guess, \(U_i(w) = w - \alpha \nabla L_{t_i}(w)\) - the basic MAML update. The authors also provide a few proofs regarding the regret.

In order to make their proofs work, the authors place a number of assumptions on the form of \(L_t\). For any math nerds out there, I’m sorry, I know that these aren’t rigorous definitions, they’re meant to be easily memorable.

- (Lipschitz in function value) : \(L_t\) has finite, bounded gradients

- (Lipschitz Gradients / \(\beta\)-smoooth) : The rate at which the gradient changes is bounded by some constant \(\beta\)

- (Lipschitz Hessian) : Same thing as above, except that it’s the Hessian being bounded by a constant \(\rho\)

- (Strong convexity) : Same thing as the second, except that we’re setting a lower bound of the absolute value instead of an upper bound.

As I read it, while this set of constraints includes logistic regression, it doesn’t include DNNs, which is a fair limitation. Within the scope of these limitations, however, the authors prove that the regret is sublinear with the number of tasks (specifically, it’s \(O(log(|\mathcal{T}|))\)). As far as I recall, this is the best regret bound that one can possibly prove, so that’s nice a solid result.

In the actual experiments, the authors make a lot of the changes that you would assume - they optimize over the minibatches saved in memory for each task using a DNN.

Experiments

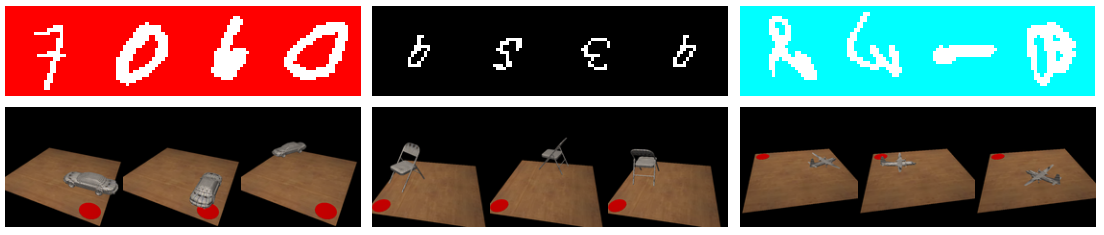

The authors evaluate on a two domains - rainbow MNIST (with colors added - shown on top) and sequential pose prediction (on bottom).

The pictures below give a pretty good idea of what they entail :

(top) rainbow MNIST (bottom) sequential pose prediction

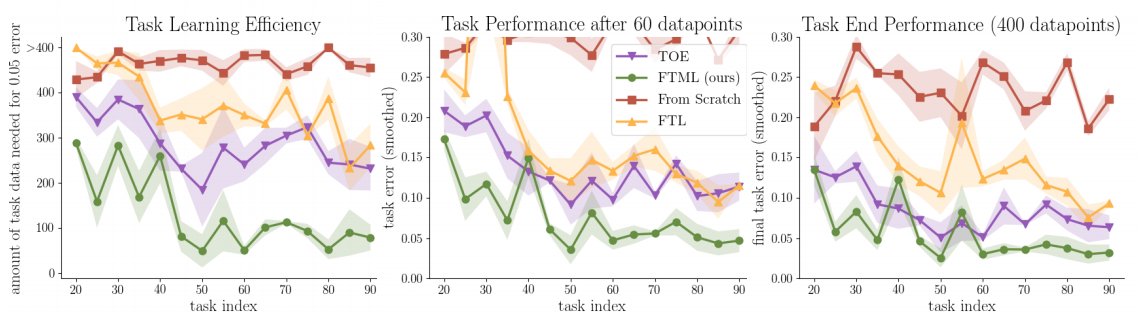

The authors compare their method (FTML) against FTL (without the finetuning step), TOE (train on everything ,self-explanatory) and and ‘From Scratch’, which, uh, learns from scratch on each example.

Below are the results for the sequential pose prediction problem, although the results for rainbow MNIST are simiilar.

These results are pretty reasonable - note that they are reporting error, NOT accuracy, so lower is better.

It’s unsurprising that FTML does better than FTL because the authors are basically letting it customize itself slightly to each task before evaluation, so it’s given a bit of a leg up.

Perhaps the most promising thing is the fact that FTML is that it learns substantially faster than FTL, which hopefully means that it minimizes interference.

Future Directions

This is an exciting domain, and I think that there is some relatively low-hanging fruit for potentially improving on it. One could try incorporating the recent paper, iMAML with it (https://arxiv.org/pdf/1909.04630.pdf), which could yield either speed or performance gains.

While meta-learning is expensive, you could also try to scale this up to larger tasks, although the computational complexity of the gradient step might be prohibitive. Finally, one could try to automatically detect distribution shift so that the algorithm can learn to identify which algorithms are what on its own.

General Thoughts

This algorithm is essentially MAML, just rebranded and applied to a different domain. That being said, it does achieve some fairly convincing results that further solidify the effectiveness of MAML. That being said, I’m not really convinced that this solved many of the core issues I see in online learning. It requires explicitly storing minibatches from all of the previous tasks and it requires explicit identification of tasks (which, to be fair, is pretty common). Additionally, it seems extremely computationally expensive, so I’m not convinced that his exact method could be used in practice.

Overall, this paper has me convinced that MAML works, but I’m less convinced that it made significant gains on existing problems in online learning.