The Computational Limits of Deep Learning

13 August 2020

Since AlexNet made world news in 2012, advances in Artificial Intelligence have created headline after headline. These advancements have largely been driven by neural networks, which have shown a voracious appetite for data and computing power. While deep learning’s demand for power has grown exponentially, Moore’s law is dead and computing speed is not increasing at the same pace. how long can this go on?

Authors

- Neil C. Thompson (Research Scientist, MIT - CSAIL)

- Kristjan Greenewald (Research Staff, IBM - MIT-IBM Lab)

- Keeheon Lee (Asst. Prof., Yonsei Univ. - Underwood Intl. College?)

- Gabriel F. Manso (University of Brasilia - UnB FGA)

ArXiV: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2007.05558.pdf

Background

It’s no secret that deep learning can take monstrouse amounts of computing power. While the original AlexNet was trained on just two (unoptimized) GPUs for a couple of days in 2012, many of the most impressive models today require huge infrastructures to even run. Models like GPT-3 and GShard use hundreds of billions of parameters. Many researchers have remarked that much of the progress in deep learning comes from increases in raw compute and data, not intelligent algorithms as we would hope. This paper tries to empiricize these intuitions via a literature review.

Core Idea

The authors begin by arguing some intuition that achieving performance improvements via raw computation quickly becomes intractable. Using a simple thought experiment, they argue that reducing the error of a model by a factor of \(n\) should take roughly \(O(n^4)\) times as much computing power. They also make a brief argument that part of why deep learning works is that hand-picking features can severely degrade performance when important features are left out, so you can often get better performance by just throwing everything in to the model. Of course, this tendency to throw everything in to the model also helps explain why deep learning can be so expensive.

The authors look at 1,058 papers posted to ArXiV performing CV or NLP on 6 standard datasets, including image classification (ImageNet) and machine translation (WMT). They try to estimate the rate at which deep learning computation increases relative to increases in performance. Their best estimate is that decreasing error by a factor of \(n\) increases the required computation by a whopping \(O(n^9)\). They extend this logic to the future - if this trend holds, the world’s current output is not enough to train a model to achieve \(1\%\) error on ImageNet. Training a model to achieve 10% error on WMT English-French translation would require us to emit orders of magnitudes more carbon than the sun has mass.

Details

The authors note that deep learning models tend to have more parameters than data, so applying all \(O(n)\) parameters to all \(O(n)\) datapoints requires \(O(n^2)\) time, even if the network trains in a single pass. In linear regressiion, the authors remark that decreasing the (rMSE) error by a factor of \(n\) requires an \(n^2\) increase in the amount of data. By this logic, they reason that the ‘theoretical limit’ to how much we can improve performance by raw data/compute is \(O(n^{2^2}) = O(n^4)\).

Experiments

The authors argue that one way to reduce these costs is to decrease the dimensionality of the problem by feature selection.

However, they note that while perfect selection is, well, perfect, if you miss a single feature it can severely degrade performance.

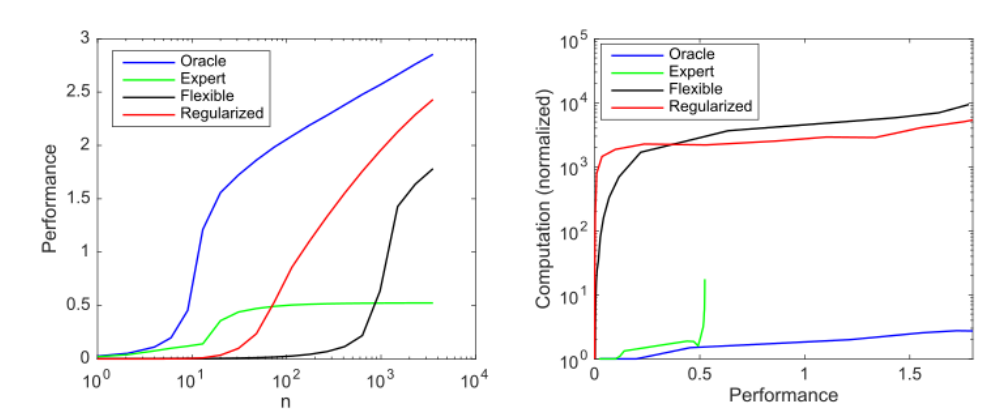

They perform some experiments on this with linear regression, as shown below :

'Oracle' represents only the 10 relevant features input, 'Expert' has 9 relevant features & one irrelevant one, 'Flexible' takes in all 1000 features and 'Regularized' is 'Flexible' but with LASSO regularization

In the experiments, they train a model for linear regression with 1,000 inputs, of which 10 are actually useful for predicting the output.

Notably, ‘Expert’ doesn’t actually do that well, but the regularized model does nearly as well as ‘Oracle’ at the cost of a BUNCH of extra computation.

In their literature review, they go beyond theoretical linear experiments to actual deep learning papers. For each of the 1,058 papers reviewed, they look at the error and attempt to estimate the cost to train the model. They do this in one of two ways:

- In papers where it’s listed, they measure the number of FLOPS (floating point operations) used to train the model.

- When the computational load (hardware burden) is listed (e.g. “Trained on 2 GTX 1080 GPUS for 16 hours), they estimate the cost as N_GPUS * TIME * GPU_SPEED

Not many papers listed the first metric, so their results are fairly sparse.

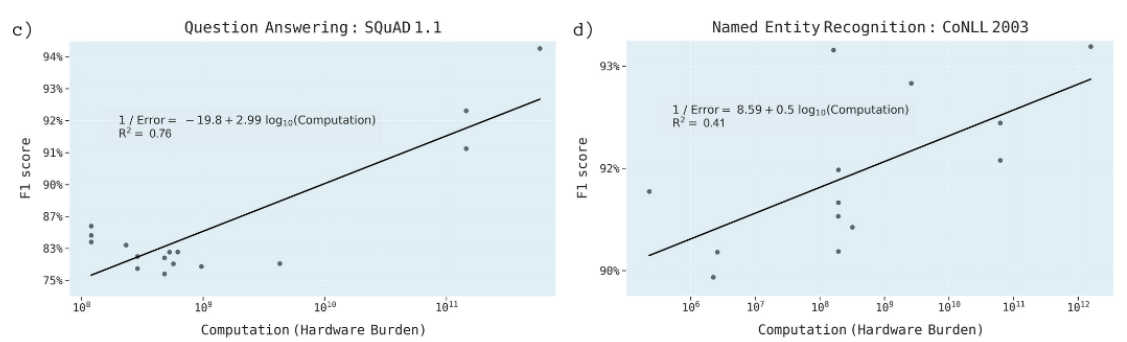

They then do linear regression on the error rate versus log of the computation power used, and they get somewhat convincing results:

I understand that it’s really difficult to get this data and also difficult to get good analysis on it, but I think it might just be too sparse to be useful.

Additionally, there are some confounding issues - you can see in the lower-left of the first graph shown, there’s actually a negative relationship shown between F1-score and computational load.

The positive relationship comes almost exclusively from the 3 outliers in the top-right.

The results in many of the other graphs also have a less-convincing fit, although the \(R^2\) values are pretty strong.

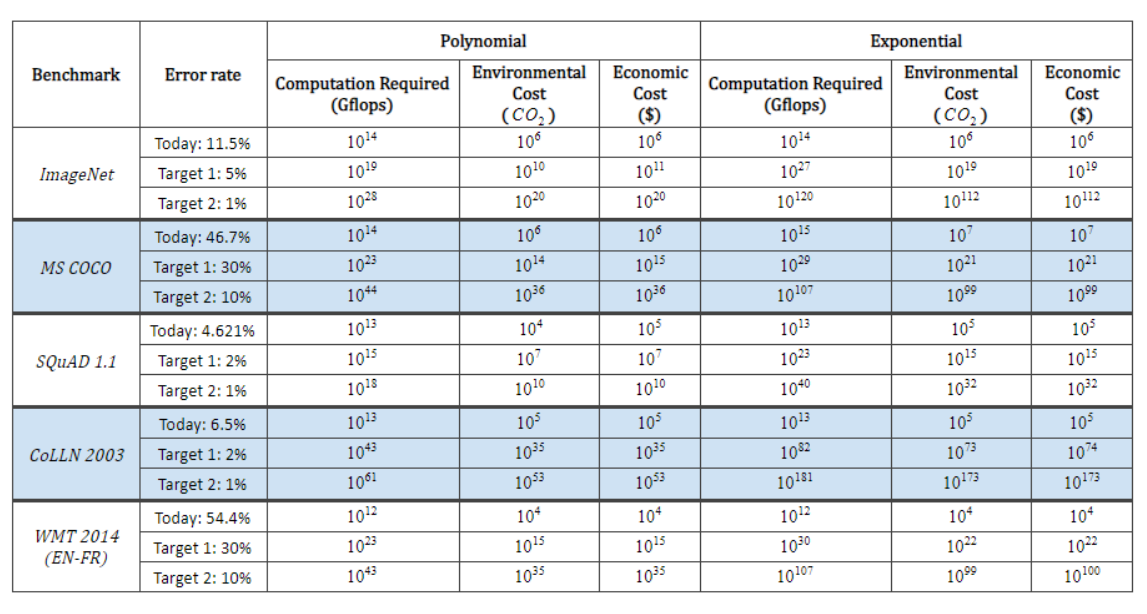

Finally, the authors extrapolate this data to give estimates for how much it would cost to train models to certain error targets given current trends.

I found it pretty interesting, so I’ll leave it below :

We can kill the world, but at least we can finally translate between English & French well.

Future Directions

The authors discuss a couple ways that we might circumvent these limits:

- Hardware Accelerators : we can improve the hardware we’re running on with anything from TPUs to quantum computing

- Reducing Computational Complexity : techniques exist to prune down the size of neural networks after training by dropping ‘useless weights’. There are also other ways to mitigate the costs of deployment

- Finding High-Performing Small Models : the authors note that neural architecture search (NAS) and meta learning can create small, efficient models, but they currently cost HUGE amounts to train

My personal take is that I think hardware accelerators will continue to give value, but they probably won’t be able to keep up with the growing costs (with the possible exception of quantum, which is a high-variance bet). Network pruning and similar approaches also help, but they don’t solve what I view to be the central problem : prohibitive training costs. I think that a version of the last option is probably the most promising - while meta-learning may be extremely expensive to train, if we can find effective ways to share the meta-learned models, it may be an effective way to decrease the computational requirements of all of the derivative models.

I think a fourth direction (which could be lumped in with the third) is finding ways to automatically drop features. I’m reminded of convolutional networks, which can be equivalently formulated as huge feedforward networks with most of the weights pre-emptively 0’d out and the remaining weights tied to each other. Technically, the representative power of these networks is strictly less than a feedforward net, but the huge savings in computational costs afforded by convolution have allowed them to easily outstrip feedforward nets in the image domain. Right now, not even NAS is close to designing such capabilities, but they could yield immense value.

General Thoughts

I have very little doubt that the author’s thesis is correct - much of the progress in machine learning has been driven by computation, and Moore’s law has not kept up. However, I’m not totally convinced that the author’s arguments are thorough enough. I’d like to see other models or data analyses to further confirm the intuitions.

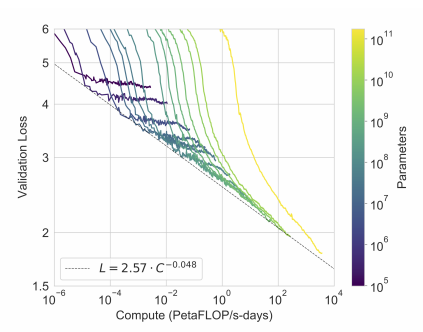

One thing that I think would be useful to see some analysis on is the chart in GPT-3 plotting loss against the number of parameters used.

Source : https://arxiv.org/pdf/2005.14165.pdf

It’s a little unclear whether these two results are compatible with each other, but some empirical validations similar to the above would be helpful in proving their case.

That being said, it makes sense that the authors didn’t discuss this specific example - the preprint (as I read it) was release 12 days before GPT-3.