Neuro-Symbolic VQA : Disentangling Reasoning from Vision and Language Understanding

13 August 2020

Visual Question Answering is the task of answering questions posed in natural language about an image. The task involves not only processing the elements of an image, the syntax of a system, but also putting them together in potentially complex ways to guess at an answer. As a result, learning modules that combine all of these aspects in to one model can be difficult. This paper proposes lightening the load on the model a little bit by using symbolic programming.

Authors

- Kexin Yi (Harvard University)

- Jiajun Wu (Asst. Prof., MIT - CSAIL)

- Chuang Gan (Research Staff, MIT - IBM Watson)

- Antonio Torralba (Prof., MIT - CSAIL)

- Pushmeet Kohli (Team Lead, DeepMind)

- Joshua B. Tenenbaum (Prof., MIT - CSAIL)

ArXiV: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1810.02338.pdf

Background

In visual question answering (VQA), the agent is provided a query in natural language with an associated image. The associated image contains all of the information necessary to answer the question. The model must then output a token representing its answer and receives a lower loss for getting the answer correct.

This paper considers two particular datasets to evaluate it’s visual question answering (VQA) prowess on: CLEVR and CLEVR-Humans. The CLEVR dataset consists of simulated images of objects where questions are generated by a program in a way that is guaranteed to be answerable. In contrast, CLEVR-Humans contains questions on the same images that were asked by real people on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (which is a cool service where you can get people on the internet to do simple tasks for you). As noted here, most existing approaches for this dataset focus on combining a CNN to parse information about the image and an RNN to parse the query.

Core Idea

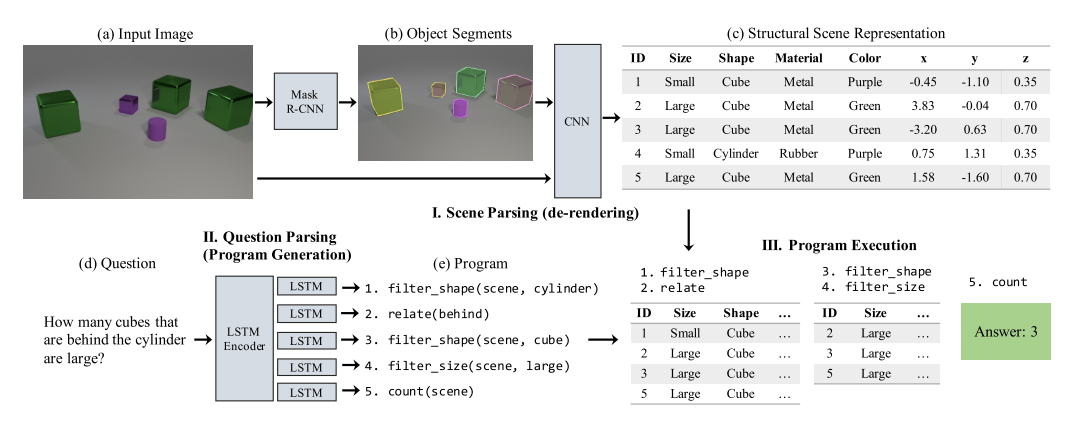

This paper doesn’t break with the standard baseline of using a CNN and an RNN to parse the image and the text respectively.

Where it does differ from existing methods is that it feeds the results of these two algorithms in to a logical executor (a traditional program) that then answers the questions.

The CNN extracts objects and information about those objects and stores the results in a table.

Meanwhile, the RNN is treated like a reinforcement learning algorithm - it looks at the query sentence and chooses what programs to invoke in the logical executor.

3 steps : parse image, parse text, chuck it in to a logic program

There is some nuance to how they do each of these tasks, but they are more-or-less what you’d expect.

Details

- Image Parser

Source: https://github.com/facebookresearch/Detectron

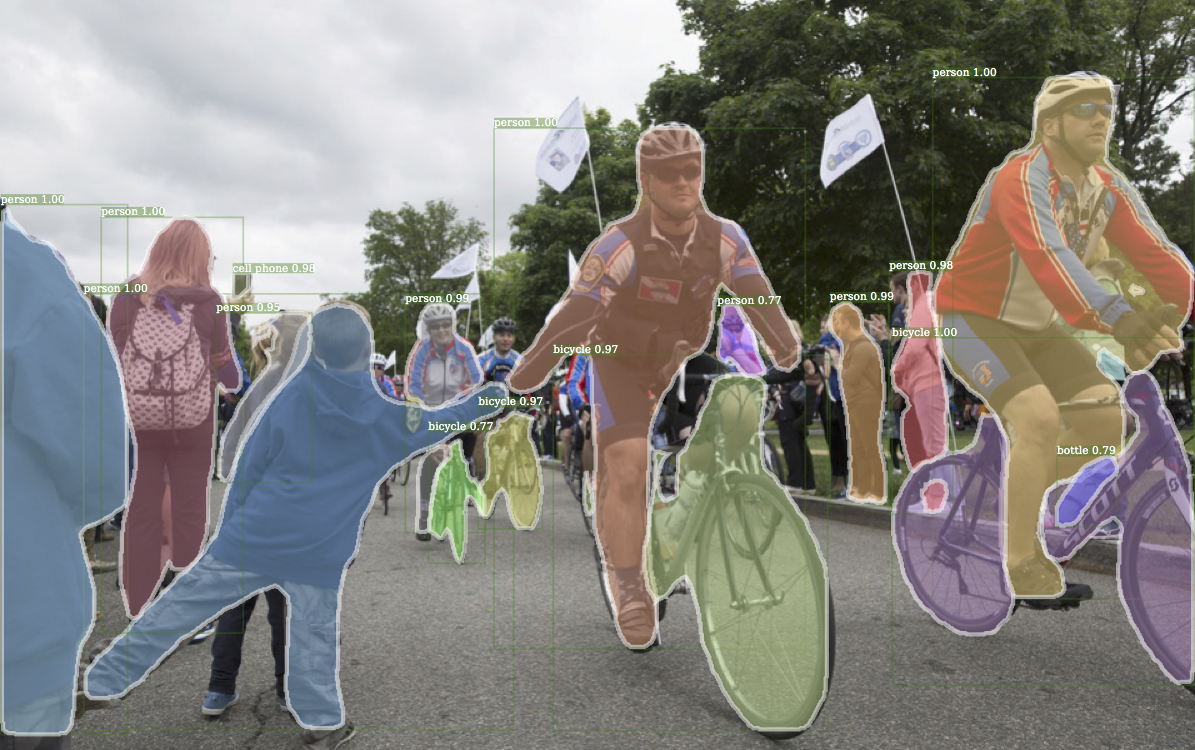

The authors train their image parser in two parts. First, they use a Mask R-CNN based off of (Detectron)[https://github.com/facebookresearch/detectron2] to find the objects in the scene (e.g. it outputs segment proposals).

They use Feature Pyramid Networks (FPNs) with a ResNet backbone for region proposal.

The model also has to output a number of relevant attributes for each object, with stuff like color, shape, etc and they drop any objects that they aren’t very confident about.

From here, they segment out the image, resize it and send it to a ResNet to extract info like pose and location.

This image all gets put in to a table, which can be thought of as a de-rendered version of the image.

Notably, the image parser is NOT trained end-to-end with the sentence parser.

- Sentence parser The goal of the sentence parser is for it to take in a sentence and output some token \(y_t\) denoting which subprogram to invoke at each point in the execution sequence.

The authors begin by encoding the query sentence using a bidirectional LSTM and then concatenated the outputs of both directions for each word. This is a pretty standard way to encode the information in a sentence.

The next part of the program is to use this encoding to choose what programs to invoke. An attention-query \(q_t\) is derived using an LSTM operating over \(y_t\), which you can think of as directing what kind of information the program is looking to derive next. This query is used to create a context vector \(c_t\) via applying attention to all of the encodings. This context is concatenated with the query, and finally input to a final layer with a softmax to decide the next \(y_t\) to use.

- Logic executor

The authors don’t give too many details regarding the implementation of the logic executor, but the code for it can be found here for those interested.

At a high level, the data computed by the sentence parser is available via a special SCENE variable that the sentence parser can pass in. If, at any point, the logical executor encounters an error, it just the whole program just outputs a random guess from the available answers, like me on every test ever.

Experiments

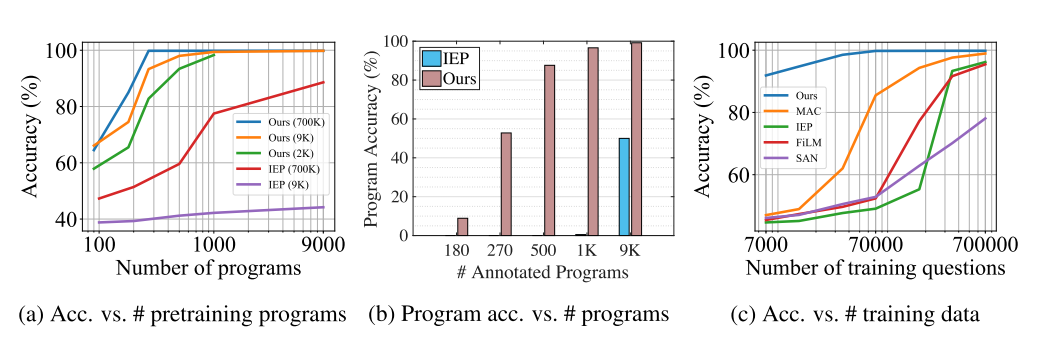

The authors start off the training of the sentence parser by having it mimic a number (270) of example programs. After that, the sentence parser is trained using a very standard reinforcement algorithm, REINFORCE. In a sense, they’re basically using imitation learning to jump-start the module to make reasonable programs, then they train it to reinforce decisions that were previously successful. The 270 samples that they jump-start with are a fairly small sample of the full 9,000 training samples, but they still give it a major leg-up.

They evaluate on the previously aforementioned datasets, primarily against a baseline called IEL, which can be found here.

In all fairness, their results do definitely substantially improve over IEL.

Of note: the y-axes of left & right graphs do not start at 0, but the gains are still substantial.

They do pretty well on the CLEVR-Humans dataset, obtaining up to a 20% increase in accuracy when there is little data.

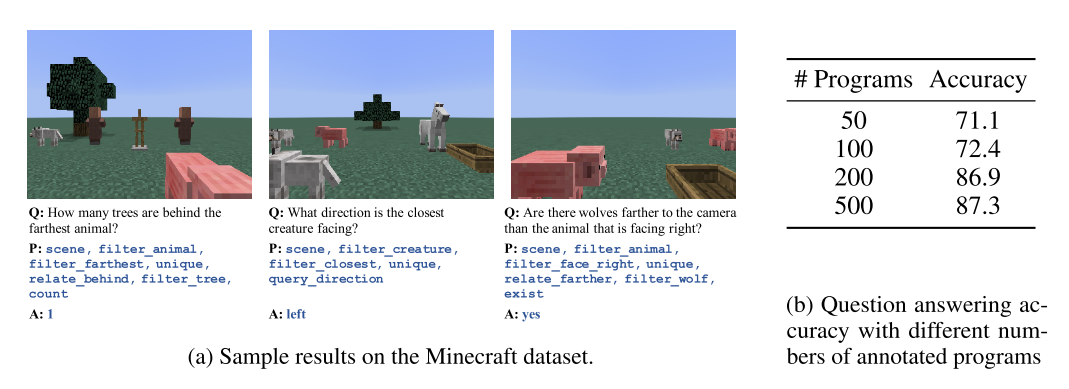

The authors also provide a Minecraft dataset, for which they’re able to get about \(70%\) accuracy with only 50 programs to mimic.

Is Minecraft still cool? It's cool in my books

Future Directions

The biggest thing lacking from this project is extensibility. It effectively handcodes a lot of the process, including special functions for filtering and counting. While these certainly work here, having to hand-code functions like these undermines one of the main benefits of machine learning - it’s ability to ‘write itself’. For instance, ‘orange’ is nowhere in the test data, and the program would be completely unable to make even the simple modification to learn about orange balls without additional coding.

Additionally, the authors observe that when there is a strong bias in the training dataset (e.g. no cylinders are red), the object detection algorithm fails to handle new scenarios well (e.g. when you see a red cylinder). They argue that this problem is contained to just the scene parser, which is true because the model is not end-to-end, but it’s still less than encouraging to me that this algorithm is truly learning disentangled relations.

General Thoughts

I like the neuro-symbolic approach, which is why I initially read this paper. I think it works to solve an interesting problem, but I don’t think really addresses many of the core problems with integrating machine learning and symbolic approaches. My biggest concern comes from the fact that the features and programs had to be hand-coded, which is not a scalable solution. One of the strong points of this paper is that it uses mostly building-block pieces : the RCNN and the RNN they used are both reasonably standard models, which makes it less likely that these results were over-engineered. They also achieve a pretty strong performance gain, which lends credence to the argument that efforts similar to this are worth continuing research in to.