Episodic Curiosity through Reachability

16 August 2020

One of the largest hindrances in reinforcement learning has been solving problems with sparse rewards: how do you know if you’re doing the right thing if you don’t get any feedback? One solution is to simply try a lot of new things - eventually you’ll find one that works. This naturally raises the question - what qualifies as new? This paper takes a stab at it by examining path length between observations.

Authors

- Nikolay Savinov (Res. Sci., DeepMind)

- Anton Raichuk (Soft. Eng., Google?)

- Raphael Marinier (Google Brain)

- Damien Vincent (Google Brain?)

- Marc Pollefeys (Res. Dir. - Microsoft AI Zurich Lab)

- Timothy Lillicrap (Adj. Prof., Univ. College - London & Staff. Res. Sci. - DeepMind)

- Sylvain Gelly (Google AI, Zurich)

ArXiV: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1810.02274.pdf

Background

Sparse rewards have been one of the core problems of reinforcement learning (RL) for a long time. In environments where the agent never receives any reward, it can be tough for it to motivate any continued searching. Similar to your roommate from college who believed life was meaningless, that same philosophy prevents it from finding the meaning in life.

One way to overcome this is by giving out intrinsic rewards. Similar to how many people just enjoy their work for the sake of their work, aspects of the problem itself can also be rewarding to the agent. Oftentimes, this can help encourage good behaviour that helps the agent explore the environment to find rewards more easily.

One relatively impactful form of intrinsic rewards has come through the implementation of ‘curiosity’, rewarding the agent explicitly for trying new things. One particularly popular implementation has come from Pathak et. Al, with an intrinsic curiosity reward based on taking unpredictable actions (for more details about the intrinsic curiosity module, click here). However, there are many elements of an environment that can be difficult to predict but hold little meaning (the canonical example is a television screen displaying static - guess what pixels will be black or white next!).

Core Idea

This paper tries to define ‘newness’ not by predictability, but by ‘distance’. They say that one observation is ‘distant’ from another if it takes a lot of actions to get from one of the corresponding states to another. For instance, as I type this, I have a lot of actions (keystrokes) left that I need to take before I finish this review, so the algorithm would say that I’m pretty far from finishing.

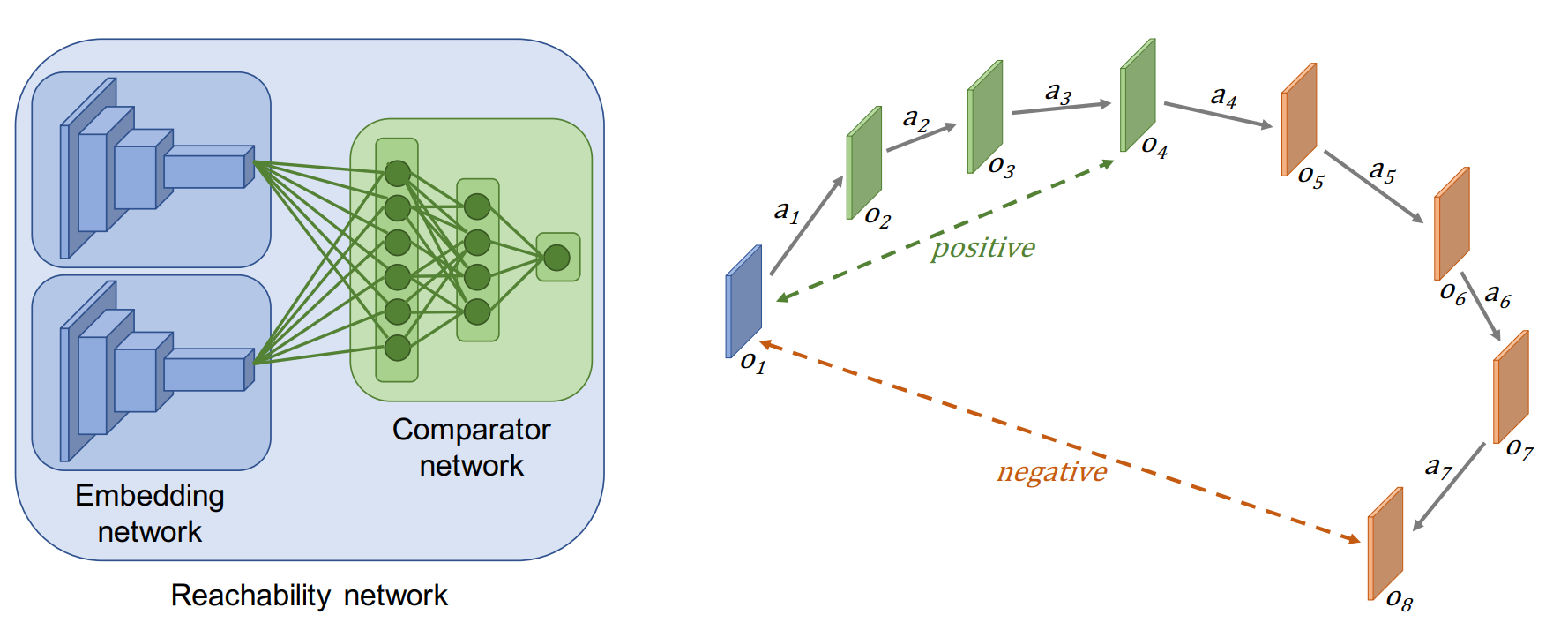

To this end, the authors train a comparator network, which they refer to as an R-network, that learns to approximate the distance between two observations.

Novel observations are stored in an episodic memory, and the agent is rewarded more if its observations are distant from those in the episodic memory.

I usually try not to think about how far away my goals are, but it's nice to look back and see how far I've come. Credit: [Dan Meyers](https://unsplash.com/@dmey503)

Details

The authors structure their R-network as a siamese network. More specifically, for two observations \(o_1\) and \(o_2\), \(R(o_1, o_2) = C(E(o_1), E(o_2))\).

In other words, they use the same network to encode both observations, then they attempt to predict the ‘distance’.

To get training samples for it, the authors take sequences of observations, and select two at random.

The classifier is then supposed to do logistic regression, classifying whether or not the two observations occurred within \(k\) timesteps of each other.

1 means that they are likely to co-occur within \(k\) steps and 0 means they are not.

The network can either be trained on random action sequences or live data (both perform similarly, live might be slightly better).

A diagram of the training scheme.

This ‘closeness’ score is computed for each observation in the episodic memory.

Note that the episodic memory is different from the replay memory - we’ll discuss how the episodic memory works in a moment.

From here, the authors need a way to combine all of the closeness scores to estimate how close the observation is to others in memory.

One might naturally assume they should use the maximum, but they said this was prone to errors due to outliers, so they used the 90th quantile instead.

From this, they’re able to compute the bonus reward \(b\)

\(b = \alpha (\beta - C)\),

where \(C\) is the aggregated closeness score and \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) are hyperparameters controlling the scale and mean of the bonuses. This bonus is added to the natural rewards, and a PPO agent is trained using the augmented reward.

Going back to the memory, observations are added to memory only when their aggregated closeness score is less than some threshold. Because we have to compare against memory at every step, they want to keep it to a small finite size. To achieve this, they kick out a random old memory whenever a new memory would be added while the buffer is at maximum size.

Experiments

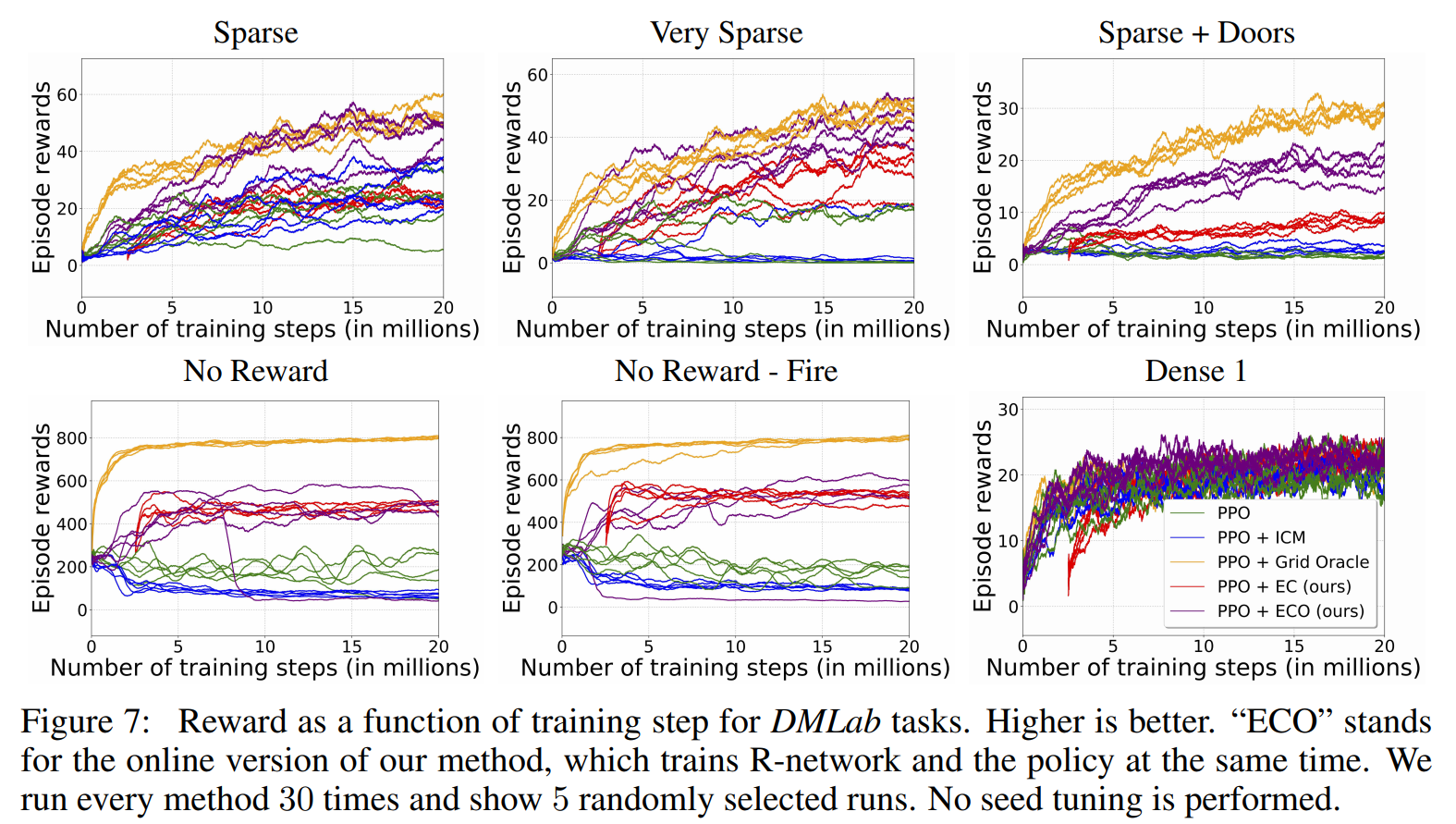

The authors experiment on a variety of environments in VizDoom, MuJoCo and DMLab.

Many of them are maze-solving environments, both static and randomized.

The authors compare their results primarily against vanilla PPO and PPO with the intrinsic curiosity module (ICM).

Their method trounces ICM in a lot of tasks, and is comparable with their oracle, which uses privileged information.

Overall, the results are quite convincing that their method learns faster than ICM on the subset of tasks that they evaluated on.

That being said, there are a number of reasons that this might be the case.

For instance, the ICM module is pretty complex and might just take a lot of time to get initialized.

Additionally, I’m not sure how well this would scale to more complex tasks, for instance, in Mario some very short action sequences can result in very unique behaviours (e.g. jumping up to hit a block), while some longer ones may not be interesting (e.g. running to the right on screen).

Finally, as I read it, their method doesn’t actually solve their motivating example with the noisy TV.

Because the module is trained to estimate guess how likely it is that two observations are temporally pretty close together, it would still likely put noisy TV screens as far apart - no two individual screens are that likely.

Future Directions

There are a couple of immediate directions where one could try to extend this work. Probably the most obvious direction is combining it with multi-episodic exploration so that it doesn’t go to the same states every episode. This would likely simply take the form of adding this intrinsic reward to another.

Additionally, you could try normalizing the distances between two states - to take the noisy TV screen example, its ‘expected’ distance between any two points on the TV screen would likely be pretty high. You could try to account for this by normalizing observations that involve the TV screen (or any other highly noisy activities), decreasing their effective distance.

Finally, it’s not immediately clear to me how this would be done, but I see the need to continually iterate through the episodic memory as very prohibitively expensive. I think that that would likely need to be eschewed in favor of a cheaper approximation for this to extend to more complex domains.

General Thoughts

I think that the direction of intrinsic-rewards for motivating explorations is really promising, and this is a reasonable take on the idea. The results are quite convincing, but I’m not totally sure how generally applicable the algorithm is. I like the approach and I think it was elegantly formulated, but I also think that there is a lot of room for this to be extended to more precisely control what we’re rewarding.