Revealing the Dark Secrets of BERT

18 August 2020

If you were looking for a paper to stoke fears that superhuman intelligence is right around the corner, this is not your paper (I recommend googling GPT-3 though). If you were looking for a paper to convince you that the field of machine learning is a sham, this is not your paper (I recommend this paper). If you were looking for a paper to get as close to science as ML ever gets, this is your paper.

Authors

- Olga Kovaleva (Res. Asst., UMass Lowell - Text Machine Lab)

- Alexey Romanov (Res. Asst., UMass Lowell - Text Machine Lab)

- Anna Rogers (PostDoc, UCopenhage - Center for Social Data Science)

- Anna Rumshisky (Assoc. Prof., UMass Lowell - Text Machine Lab)

ArXiV: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1810.02338.pdf

Background

At this point, BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) almost needs no introduction. It’s so popular that it’s the first results that shows up when you search Bert on DuckDuckGo, ahead of all of the people out there that are actually named bertrand. It has inspired a bunch of other language models to continue the trend of naming language models after Sesame Street characters (there is literally a BERT, ERNIE, KERMIT, Grover and Big BIRD). For a high-level overview, BERT is a transformer that is pretrained by predicting masked words in a sentence, and then can be fine-tuned for various tasks. But, like much of deep learning, how it actually works is a bit of a mystery … it’s kind of a black box. Lucky for us, attention models admit a fairly easy form of inspection … looking at where they place their attention. This paper seeks to answer several questions on that topic.

Core Idea

The authors ask (and attempt to answer) three main questions in their work.

- “What are common attention patterns, how do they change during fine-tuning, and how does that impact performance?” (OK, that’s technically three right there).

- What linguistic knowledge is encoded in self-attention weights of the fine-tuned models and what portion comes from BERT’s pretraining?

- How different are the self attention patterns of different heads?

Their basic findings are as follows.

What are common attention patterns?

The authors identify 5 common patterns.

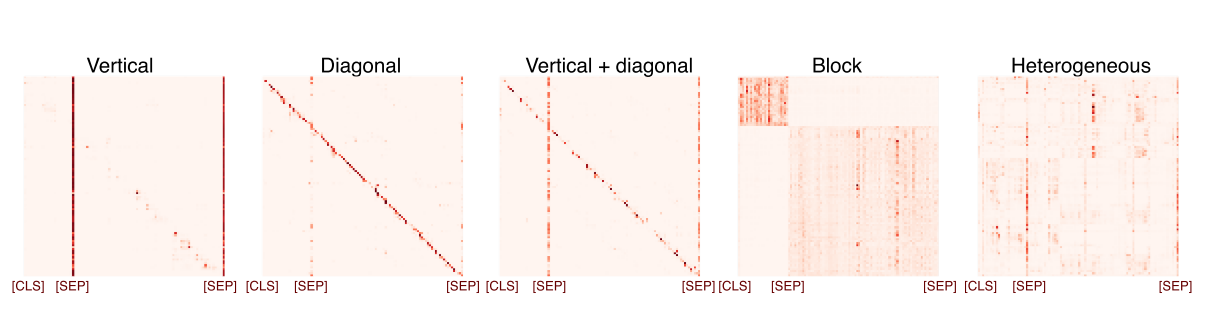

They visualize them by creating a matrix and plotting how much each head pays attention to each other head, as shown below (darker means more attention).

Heterogeneous is a nice way to say 'we couldn't find a pattern here

Of note, the heads with block attention are usually just paying attention to their own sentence when there are multiple sentences (when visualized as a matrix, this results in a block effect.)

Diagonal means that they’re paying attention to themselves and their neighbours, vertical means that everyone’s paying attention to some tokens in particular (usually the CLS and SEP tokens).

For reference, the CLS (class) token is a token that’s thrown in at the beginning of the text, and it’s output is used for classification.

The SEP (separator) token is inserted between sentences.

Most of the attention heads are either heterogeneous or have vertical attention, with diagonal and block attention being the least common.

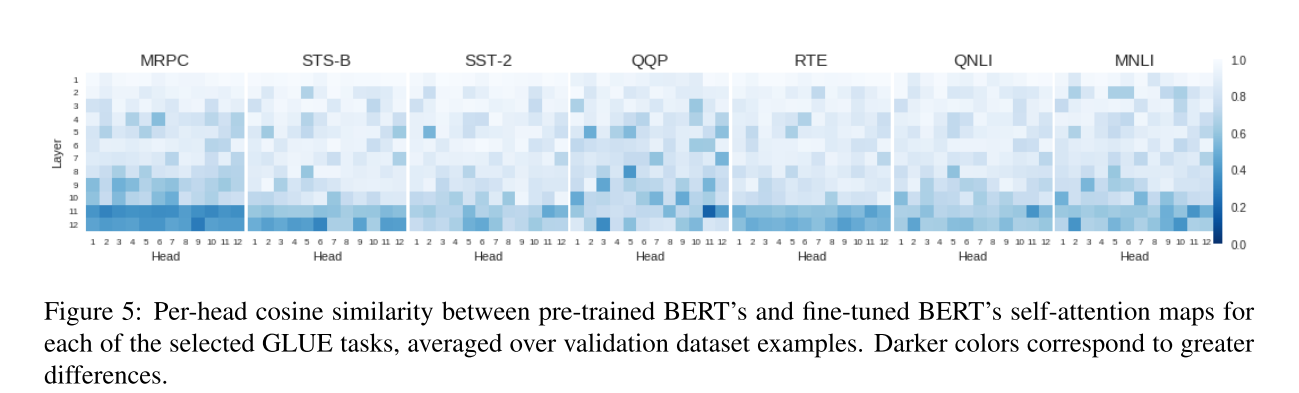

They also note that the later layers tend to change more during fine-tuning, as shown in the graph below :

What linguistic knowledge is encoded?

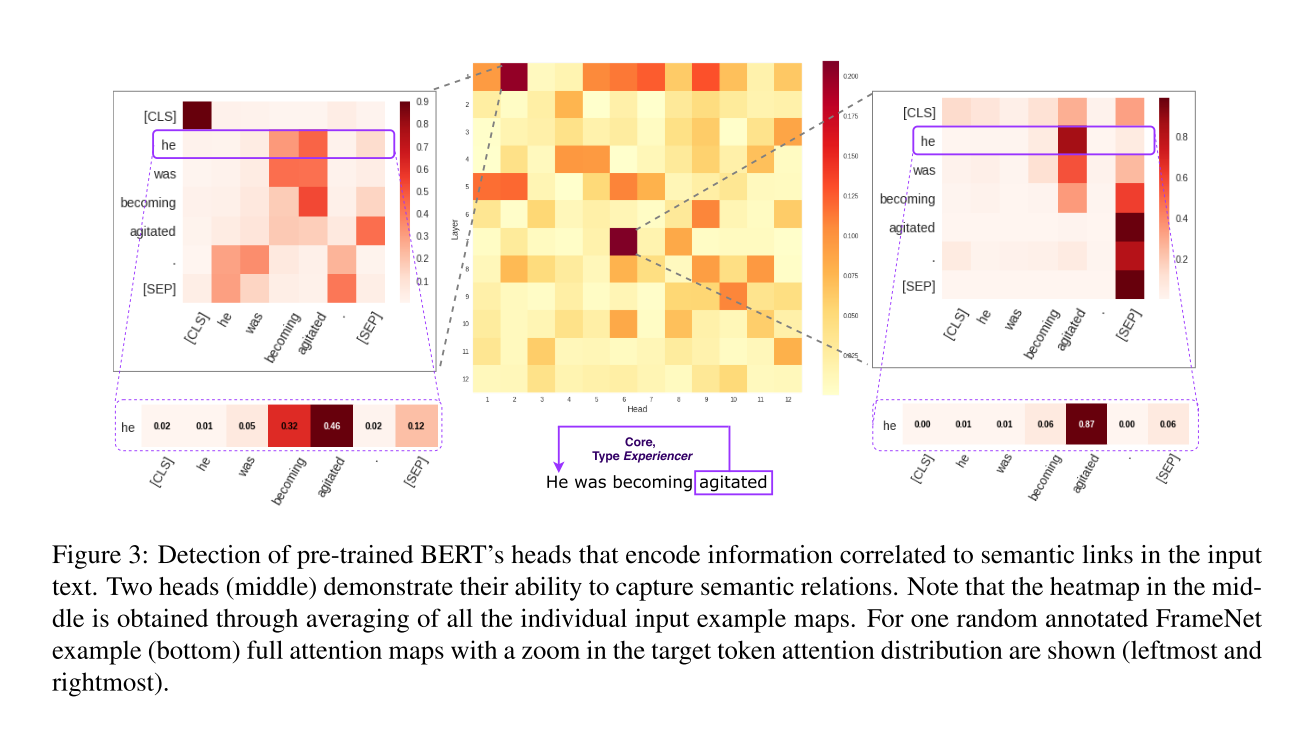

The authors use data from FrameNet, which annotates the roles of different parts of the sentence, including what is referring to what (example below).

Their results show that only two heads (of 144) actually tend to attend to what FrameNet marks as the core elements of a sentence.

These two nodes get a lot of attention from other nodes though - they’re in the 99th percentile when averaging received attention over multiple queries.

What are different patterns in different heads?

A lot of heads pay a lot of attention to themselves and their neighbours. The authors attribute this to the fact that adjectives are usually near their associated nouns and similar constructs of locality in English. This seems like a reasonable argument to me.

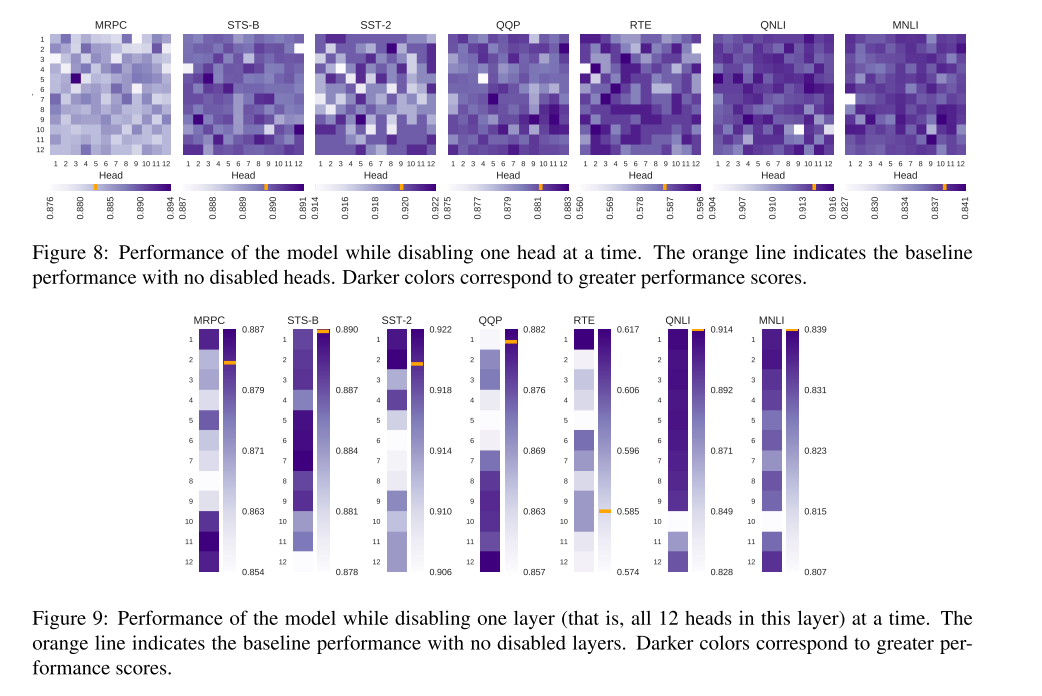

I may have lied when I said that there’s nothing that will shake your faith in machine learning in here. The authors try an experiment where they turn off attention heads (by literally just replacing them with the averaging operation) and they find that this improves performance sometimes. What’s more, for some tasks, you can expect to improve your performance by turning off random heads. While it’s not a huge deal, it definitely indicates that our current models might be significantly overparameterized, although it’s not clear what to do with it.

Details & Experiments

When examining the types of attention, the authors begin by manually annotating attention patterns. After selecting a number of representative samples, the authors trained CNNs to classify the rest of the attention patterns, using the manually annotated ones as training samples. I’m not sure that I love this method, because there are multiple layers of error - what the humans catch and how those errors are propagated through the machine learning model. You could definitely argue that these issues are there in all of the work in our field, I think I would have preferred at least solidifying the second part by mathematically characterizing the classification process.

To look at how much the layers change over the course of the fine-tuning process, the authors calculated the cosine similarity between the attention weights before and after fine-tuning, and averaged over the input samples for all of the datasets. For all of these analyses, the authors used 6 different datasets: MRPC, STS-B, SST-2, QQP, RTE, QNLI, and MNLI. I’m not personally an NLP guy, so I can’t comment on their choices of datasets, but their results seem pretty consistent across datasets and include nearly all of the GLUE (General Language Understanding Evaluation) benchmarks.

Finally, to ‘turn off’ an attention head, the authors simply force it to pay uniform attention to all of the inputs.

I think their results here are pretty well-presented, and quite surprising.

Shockingly, you can turn off entire layers and still increase performance.

This is pretty similar to what they did in “Hopfield Networks Is All You Need” (links 1, 2, 3 ), where they noted that a lot of the layers basically just perform averaging.

I believe that this paper is the first to note that fact, but HNIAYN gives good intuition.

There are a few other experimental results of interest in the paper, so I recommend interested readers to go take a look at the full paper!

Future Directions & General Thoughts

I think that this kind of work is highly underappreciated within the machine learning community. Having understanding like what this paper gives is useful for building an intuition about how networks perform, and allows us to diagnose problems a little bit better. I don’t know that I’m the best person to do it, but I think that building a library of similar results could actually be a huge asset for learners, so that people don’t have to acquire the information on their own through years of experience. One could imagine similar studies asking what questions in reinforcement learning are ‘hard’, how network capacity affects performance, or how similar two tasks are by looking at the similarity of their attention mechanisms. I’m sure answers to some of these questions are out there, but they seem to be mostly passed around the internet in the form of casual knowledge or rules of thumb. Some experiments to quantify these problems could lead us closer to a theory of machine learning, which could hopefully give us a way out of the pattern of continually throwing more compute at harder problems.