Recurrent Independent Mechanisms

19 August 2020

Some of the greatest leaps forward in neural networks have come from removing connections instead of just adding them. Convolutional Neural Networks reduce connections to maintain translational invariance, LSTMs limit interference with their long-term memory and GShard uses sharding to save computation. A lot of scientific models are predicated on similar principles to model the world : \(f=ma\) doesn’t ask you to know the pressure surrounding the object it’s modeling. Recurrent Independent Mechanisms take a step to extend this principle by creating weakly-interactive recurrent models for objects.

Authors

- Anirudh Goyal (PhD Cand., UMontreal - MILA)

- Alex Lamb (PhD Cand., UMontreal - MILA)

- Jordan Hoffman (Res. Sci. - DeepMind)

- Shagun Sodhani (Master’s, UMontreal - MILA)

- Sergey Levine (Asst. Prof., Berkeley - BAIR)

- Yoshua Bengio (Prof., UMontreal - MILA)

- Bernhard Scholkopf (Director, Max Plank Institute)

ArXiV: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1909.10893.pdf

Background

The idea of slicing up neural networks in to submodules is not new. From routing networks to EntNET to GShard, many different papers have worked to realize the possible benefits that modularization could provide. To list a few, modularization can reduce the number of parameters that need to be learned, reduce computation, improve explicability and potentially even allowing for subnetwork reuse. A lot of the time, this work coincides with work that attempt to allow networks to interact with some form of memory to more closely mimic some of the strategies that have been successful in programming.

For instance, if you think of the conditional execution of submodules as using if-statements to execute different functions, the relationship becomes more clear. Anyone who’s even touched programming probably cringes at the thought of writing any reasonably-sized program without functions or conditional execution. These abstractions can help make the code A LOT simpler and easy to manipulate.

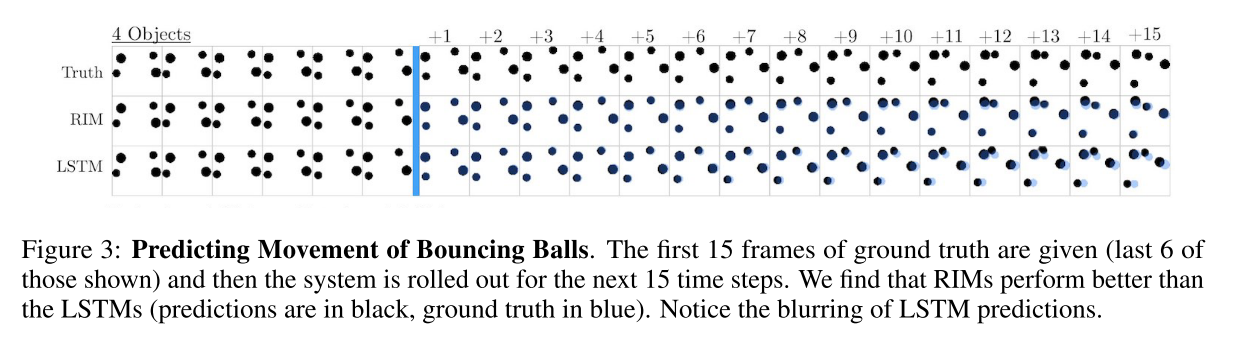

The authors motivate this work with an example of modelling bouncing balls. Intuitively, the bouncing balls can be independently modified most of the time, only occasionally interacting with each other when they touch. One would naturally try to model this by modelling each ball separately and only having their states interact when they collide with each other. This frame leads us pretty naturally to the author’s core ideas.

Core Idea

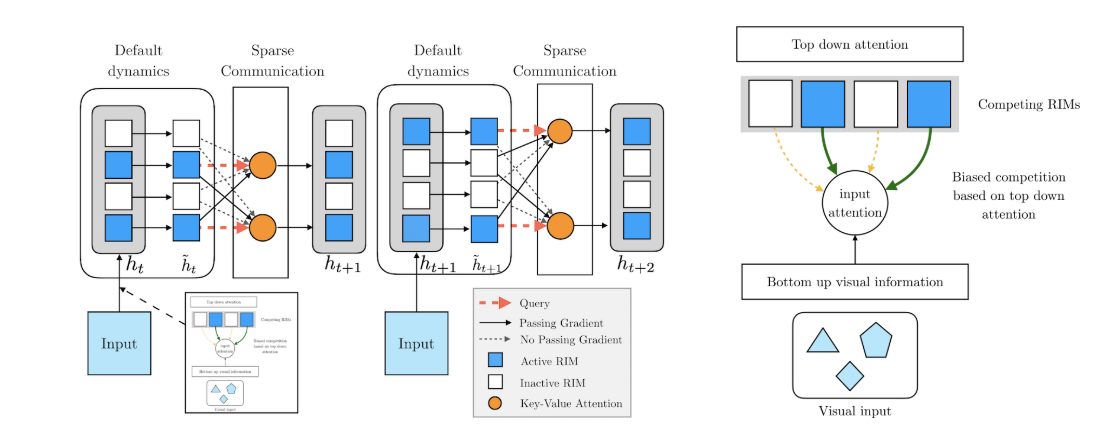

The authors propose slicing the data to create sets of vectors, which represent what one could think of as variables in a traditional program. Each of the functional ‘modules’ (mechanisms) are simple RNNs that take in an input and spit out an output. At each timestep, these modules get to query the ‘variables’ to choose which ones they want to pay the most attention to. One interesting aspect of this project is the fact that they give the modules the chance to pay attention to nothing at all, by presenting the 0-vector as a possible attention target.

So, now that we’ve covered the base-idea of separate recurrent modules paying attention to different parts of the input, it’s time to talk about the second big thing : competition. At any given time, not all of the modules (which the authors call RIMs) are paying attention to real data: they’re all devoting some amount of attention to the 0-vector of non-data. The authors select the \(k\) RIMs that are paying the most attention to real data and they turn the others off, so that they perform no computation. Their hidden state stays the same, and none of the data is sent to the network (although gradients can still flow through the hidden state during backprop). The authors motivate this with real-world biology, where our brains have limited computational resources that are available to be used, so they can’t do everything. This mechanism lets the different RIMs/modules compete with each other for computational resources.

If you’re paying attention, you might have noticed that we haven’t yet introduced a way for the modules to interact with each other.

This last step is done in a pretty intuitive way: the different RIMs are all given the opportunity to pay attention to each other’s hidden state when updating their own.

Put it all together and it looks something like this.

Details

The attention-to-data process works basically like you probably intuit: a set of vectors \(X\) are input to the system, a 0-vector is added to the set, each vector undergoes the standard linear transformation to become keys \(K_d\) and values \(V_d\). The one (minor) twist is that this isn’t self-attention, so the queries \(Q_d\) come from the RIMS, again by simple linear projection of their hidden state.

The attention-to-each-other process is again similar to what you’d expect, except that this one is true self attention: the keys \(K_h\), values \(V_h\) and queries \(Q_h\) are all computed as linear projections of the hidden states. The updated hidden states are then the output of this self-attention module added to the original hidden states. Adding the original hidden state back in makes sure that each module’s hidden state pays the most attention to itself.

One last thing to note: although I explained the process in terms of sequentially processing timesteps, the problem doesn’t need to be temporal - it can be any sequence, like a sentence in NLP. In NLP, you could think of each RIM as keeping track of different parts of the sentence - maybe one tracks the subject, another tracks the object, etc.

Experiments

The authors provide a good range of experiments.

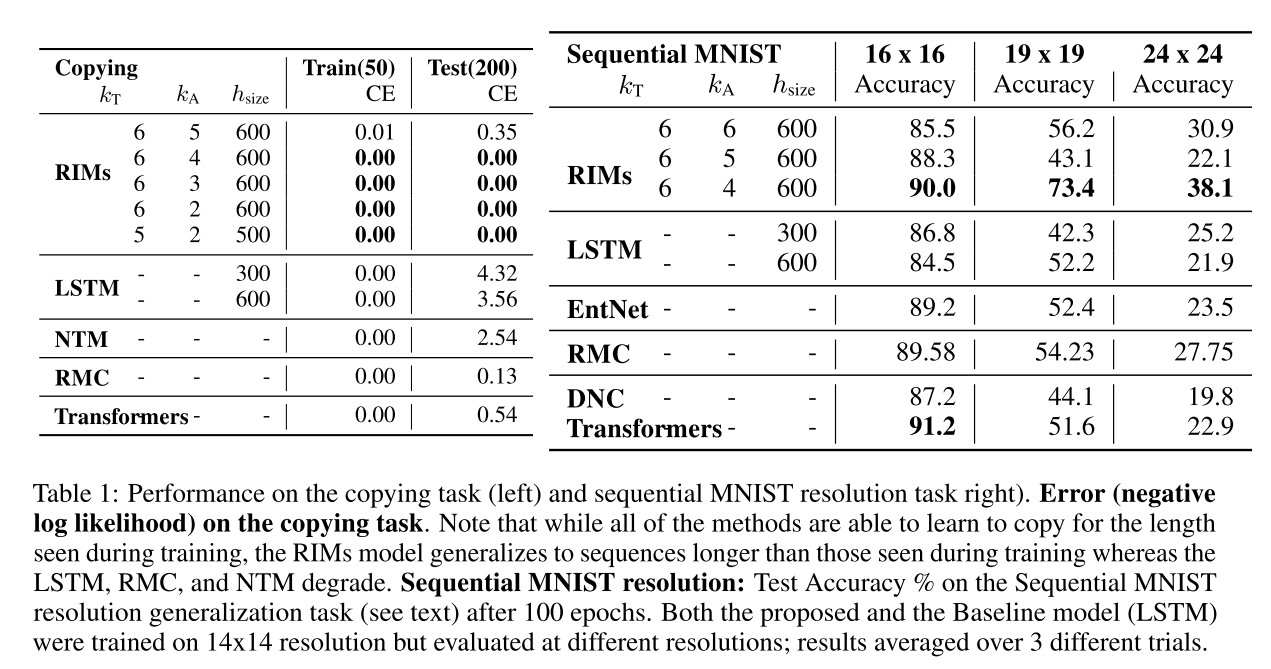

The first experiment is the canonical copying task that we often see from memory-based models.

The model is given a sequence of inputs that it has to remember, then it receives white space for a number of timesteps, and finally it’s asked to repeat the initial inputs.

Intuitively, it just has to copy the inputs after some delay.

The authors show that their method substantially outperforms an LSTM:

I'm not sure if this is a fair example though : you'll note that because they have multiple RNNs, the RIM models have more parameters than the baseline LSTM. For reference, NTM refers to 'Neural Turing Machine' and RMC refers to 'Relational Memory Core.'

They next use a bouncing balls environment, where the model has to keep track of the position of a number of balls.

For all the reasons that the authors specified in their motivating example, we would naturally expect RIMs to do pretty well here.

They do (I’ll save you from having to look at the graph).

One particularly notable thing is that their model does pretty well, even when a different number of balls are used during training and testing. Unfortunately, that (presumably) only goes one way - you can decrease the number of balls in test, but not increase them.

Finally, they compare their method to an LSTM operating on PPO in Atari gym.

This gives the attractive graph shown in the header.

Attractive both graphically and analytically - good results.

I briefly looked through the appendix and I wasn’t able to find the details for the LSTM they used as a baseline here.

My one concern would be whether or not it’s a level playing field - the RIM model might just be given more parameters to work with.

Another thing to note is that you do need a number of RIMs to achieve a substantial performance boost - they did an alternate test with 4 RIMs instead of 5 and the results are less compelling.

There are actually A LOT of results here (in addition to some ablations), so it’s really hard to criticize them on that, which is sweet.

Future Directions

This work is still in progress, and the authors list a number of potential modifications to their algorithm. They say that it would be interesting to explore different ways to control which RIMs activate. The authors also discuss providing the agent’s previous actions and rewards to the agent as input in RL environments. When they have to decode the outputs of the RIMs, they presently just concatenate them all (which is basically the default) and they remark that they’d be interested in finding a more structured way to combine these.

General Thoughts

I think that RIMs are a solid approach to the problems that the authors seek to solve. The way that they constructed all of the parts of their module seem pretty reasonable, and their results are pretty extensively logged in the appendix. My one point of disagreement with the authors would probably be in their initial desiderata. The authors explicitly stated that they want each module to have different dynamics, and so they have different parameters.

In a lot of scenarios, that might not be the best approach - for instance, their motivating example with bouncing balls. While each ball does have a different state, they all share the same underlying dynamics. I don’t think anyone has solved this problem, but figuring out when two objects have the same dynamics seems like the next big step to me. This could allow parameter sharing and substantially increase robustness.

My other big concern is with their competition mechanism. Because the hidden state stays constant when a module is ‘turned off’, it’s not learning. One could very easily see a situation where some RIMs initially pay less attention to the 0-vector, and are therefore turned on more often. These modules get trained more and continue to dominate the competition, which may leave other RIMs largely unused. This effect is somewhat similar to the exploration-exploitation problem in RL (I’m far from the first person to make this observation) and I think that it could severely hamper these models in the future.