Episodic Control as Meta-Reinforcement Learning

21 August 2020

As the deep learning community grapples with the ever expanding costs of training ever-larger models, a number of possible strategies for circumventing these problems have emerged. Among them, meta-learning (or ‘learning to learn’, a term we apparently stole from psychology) hopes to find ways to speed up the learning process by jointly learning about multiple processes. In reinforcement learning (incidentally, another term stolen from psych), episodic control leverages short-term memories to, you guessed it, learn more efficiently about the environment. This paper frames the episodic control as a form of meta-learning (literally the title) and provides a new memory structure aimed at accommodating this relation.

Authors

- Sam Ritter (Res. Sci - DeepMind)

- Jane X Wang (Res. Sci - DeepMind)

- Zeb Kurth-Nelson (Res. Sci. - DeepMind)

- Matthew Botvinick (Dir. NeuroSci Res. - DeepMind)

Link: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/360537v1.full.pdf

Background

In meta-learning, a model is presented with a series of tasks that share some joint underlying structure. This paper phrases the problem in terms of the bias-variance tradeoff : traditional neural networks have tons of parameters and therefore high variance. This has the benefit that they can fit nearly anything, but the downside that they require a ton of data to achieve this goal. The flipside of this is a high-bias model, which has limited representational ability but requires less data to train its fewer parameters. Through this lens, the goal of meta-learning is to use a single high-variance model to learn a format for high-bias models that are able to fit each of the tasks well. Intuitively, this should work because collectively, there might be enough data for the high-variance model, but each individual task might only have enough to fit a highly biased model well.

Flipping over to the domain of reinforcement learning, we have the idea of episodic control. This usually involves non-parametric methods that explicitly deal with all of the observations that the agent has seen within that episode : for examples of this, you can look at ‘Never Give Up’, which I reviewed recently. Intuitively, if the starting parameters of each episode are randomized, you could view each start as a different task inside of the meta-problem that is the environment. Learning to solve the given start position then amounts to identifying what the parameters of the environment you are in are, and then using your knowledge about how to navigate the environment in general to solve the problem.

Core Idea

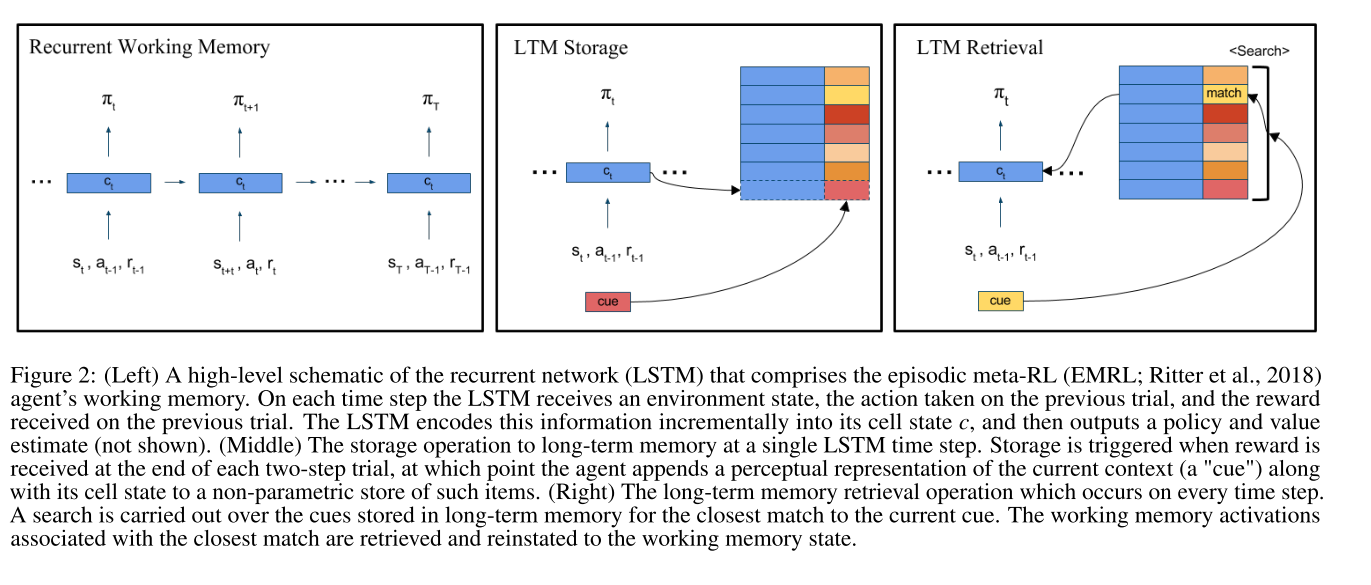

The authors cite research in psychology that suggests that humans and other animals use selective recall (which they term ‘reinstatement’) to solve new problems where old information is relevant. They propose a 3 part process for reinstatement in the RL environment:

- Keeping an explicit episodic memory

- Use a key-value encoding for the memories (where the keys are the observations and the values are the hidden state - more on this later).

- Gating the retrieved states in to some active model that controls dynamics

Traditional recurrent units (e.g. LSTMs or GRUs) typically calculate their output in terms of their hidden state \(h_t\) and the observed input \(x_t\).

This paper proposes adding a third argument - provided by the explicit memory.

Namely, they save each pair of \(x_t\) and \(h_t\).

When they come across a new observation, they check for the closest observation \(x_i\) and return the corresponding \(h_i\).

This is then incorporated in to the recurrent module similarly to the other elements, as described in ‘Details’.

Intuitively, this should provide the network with a way to explicitly conjur up related memories and use their associated context to make decisions.

Details

Not too many details to list here, most everything works how you think it does. They note that the traditional recurrent mechanism roughly looks like

\[h_{t+1} = g_1 \cdot h_t + g_2 \cdot x_t\]Where \(g_1, \ g_2\) are the gating mechanisms, each computed by \(g_1=\sigma(W^{\{1\}}_xx_t + W^{\{1\}}_hh_t + b)\) (and same for \(g_2\)). Their addition is to basically update the equation to be

\[h_{t+1} = g_1 \cdot h_t + g_2 \cdot x_t + g_3 \cdot h_{ltm}\]where \(h_{ltm}\) is the stored hidden state to the layer, as described previously. Of note, the non-parametric memory isn’t strictly nonparametric, because the ‘observation’ recorded for each hidden layer is just the inputs to that layer (which is a learned representation itself). \(g_3\) is computed in exactly the same way as \(g_1\) and \(g_2\), except with its own weights. Interestingly, they don’t actually update the gating functions : one would anticipate that the gating function should also incorporate \(h_{ltm}\) in its calculation, but they don’t (even though that may affect \(h_{ltm}\)).

Experiments

The authors use a fairly unique experiment for their method. I appreciate it for the fact that it does distill the problem down to just what they’re testing, but it would be nice to see whether or not their approach works in real-world scenarios as well.

To summarize, they propose an environment where the agent either receives a cue or it doesn’t. If they don’t receive a cue, then they take an action that leads the agent to one of two states and then it receives a reward. The state is provided as a set of 1’s and 0’s, because we’re computer scientists. If the agent does receive a cue, it’s a previous state. This informs the agent that, if it does the same action that led it to the state with the same representation as the cue, then they will end up at that state again (with the same reward as they got last time). Whether the agent realizes this or not is up to the agent.

This experimental setup basically encourages the agent to go back in to its memories, remember what action led to the state being shown in the cue and decide whether or not it wants to take that action. It may not want to take that action, because the associated state might give a low reward, in which case it can take the other action to get essentially a random reward. There are only ever two actions, and the states are pretty small and simple. This process repeats 100 times, forming an episode. All algorithms are trained using A2C.

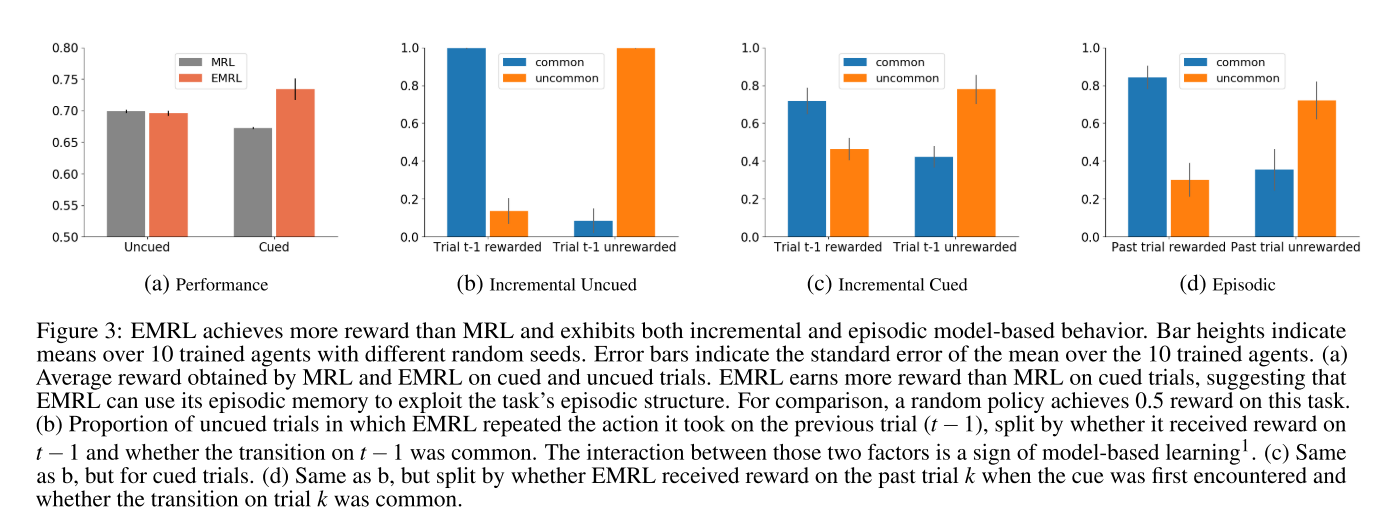

They test their agent (EMRL) against the same agent with the episodic component removed (MRL).

To make sure that the agents can’t just use recent memories as cues, no observation is used as a cue until 25 trials after it’s first seen.

Turns out, if you create a task asking you to (more or less) explicitly recall memories, the agent with explicit memory recall built in does better

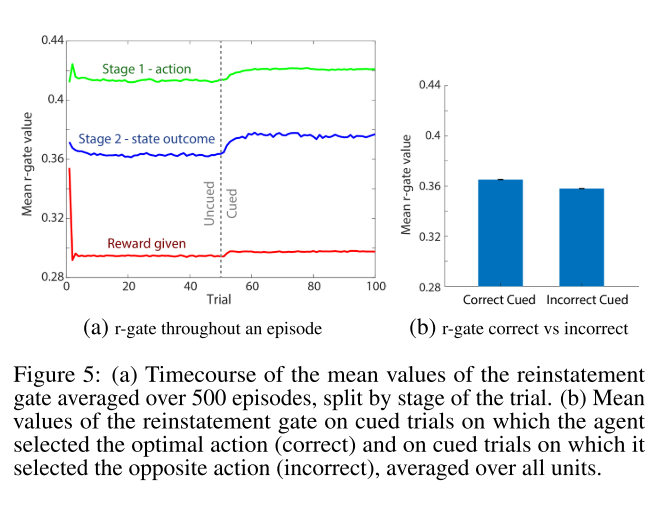

The authors also show that the agent also pays more attention to the episodic memory module during the portion of the episode where it receives cues (which is the portion where the episodic memory is useful).

While the change is marked, it's actually not as dramatic as you would initially assume.

Future Directions

The authors suggest testing whether or not the agents exhibit biases similar to humans when tested in other environments (I get the sense this is something that they might pursue in the near future). To me, the biggest question mark is how often the benefits of this agent actually come in to practice. The authors clearly and cleanly showed a scenario where it outperforms a baseline, but it’s not totally clear how often this skill is necessary in practice. Additionally, there aren’t really any other baselines - for instance, you could make a pretty strong argument that using an attention mechanism over an LSTM or GRU would alleviate the problems they highlighted in recurrent units just as well as their algorithm does. As an additional nitpick, I just don’t think that the non-parametric method is feasible in the long-term, as these problems scale up in size. It’s possible that there are some good engineering tricks to speed these up, but I see a lot more papers proposing non-parametric methods than I see papers speeding up non-parametric methods.

General Thoughts

I actually really liked this paper. I appreciated the biological motivation, and I definitely agree with the author’s general framework for reinstatement. It provides a nice way to work on episodic problems, and they phrase their episodic control in the context of meta-learning well (although I’m still not convinced I would say that their experiments demonstrate meta-learning). I recognize that this is largely a theory paper, and the authors do provide some very solid statistical analyses in their experiments that I didn’t have time to go over (I recommend checking them out!). That being said, I think that any experiment needs solid baselines to understand its impact, and I’m not very clear where the paper sits on that front. In total, I think this is a clear-headed approach to a very important problem and it leans on some more classical scientific methods of proving its idea. I just wish that it were easier to put in to context of the larger discourse in machine learning.