Program Guided Agent

24 August 2020

Most of the great companies of the world today are built on code written by humans. A lot of the time, problems that are easy for people are difficult for computers and vice versa (Moravec’s Paradox). You might naturally ask - could we save machine learning some of the work by explicitly programming part of its behaviour? This paper seeks to find out.

Authors

- ShaoHua Sun (Phd Cand. - CLVR, USC)

- TeLin Wu (Res. Asst. - CLVR, USC)

- Joseph Lim (Asst. Prof. - CLVR, USC)

ArXiV: https://openreview.net/pdf?id=BkxUvnEYDH

Background

If you’re reading this, it probably isn’t news to you to hear that it can take a lot of resources to train an ML model. You have to create a mechanism for it to get data, you have to specify a reward function, you have to sterilize the inputs, etc. This is often-times non-transferrable, meaning that it has to be done (largely) separately for each task.

Wouldn’t it be wonderful if we could just tell the model what we want?

People have tried similar ideas many times, with different strategies such as offering a prompt which can indicate the task to an agent, or having a model try to replicate the inputs and outputs of code. These can have problems because natural language can be imprecise and, as for the code … how many times are you going to run in to a scenario where you write a piece of code and yet you still need an ML model that does the exact same thing? There has also been work in teaching agents by providing demonstrations, but providing a demonstration can often be expensive and may not cover the topic in full generality.

Core Idea

The big idea here is that you write a program, and you have models fill in the parts that you “don’t want to write”. This could be useful in scenarios interacting with the world, where machine learning handles perception much better than hand-written code. You could keep the things that are naturally expressed with as logic (traditional code) and environmental interactions as ML code. To this extent, the authors identify two types of statements that might requires a network:

- Perception : identifying what’s in an environment

- Policy : acting in the environment

The idea is pretty simple : you have a core program interpreter that functions like a normal program, but then it has several points where it calls one of the two networks.

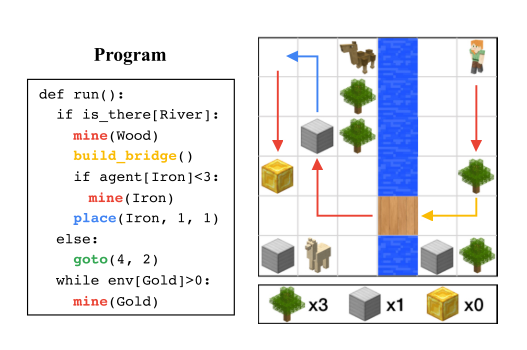

A schematic of a program is shown below:

I appreciate that they stole minecraft sprites for their environment.

The perception network (currently) only gives back 1’s and 0’s indicating whether a queried object is in the environment.

The policy network is a fairly standard A2C algorithm where a goal state is specified and the agent is provided with reward upon reaching that goal.

This is (in my opinion) all very standard, I think that the paper’s largest contribution is their model design, which makes a lot of sense.

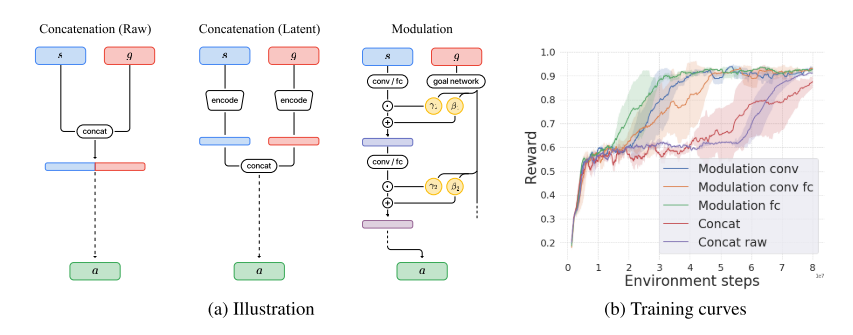

I'm honestly just including this image because people like images, they're useful.

Details

We can look at the perception network like a function isPresent?(Query, State), asking something about the current state. The policy network can be phrased in a similar way : achieveGoal(Goal, State). You’ll note that both of these take two arguments: the state and something else. The natural question is how to combine these inputs when we chuck them in to the neural network. The standard way would probably be to just concatenate them, which is valid.

However, concatenation is limited in its representation power. Consider a network that of the form

\[g(x, y) = \sigma(W_1\vec{x} + W_2\vec{y} + \vec{b})\]This is equivalent to what you get when you concatenate the inputs. No matter what value \(y\) has, the effect will always be the same as if we had just chosen a different bias \(\vec{b_2} = W_2\vec{y} + \vec{b}\), which means it’s limited in representational power. This effect applies even if you initially process both \(\vec{x}\) and \(\vec{y}\) separately: whenever you put them together via concatenation, it’s the same as just adjusting the bias. The same is true if you use addition instead of concatenation (that would be the case where \(W_1 = W_2\)).

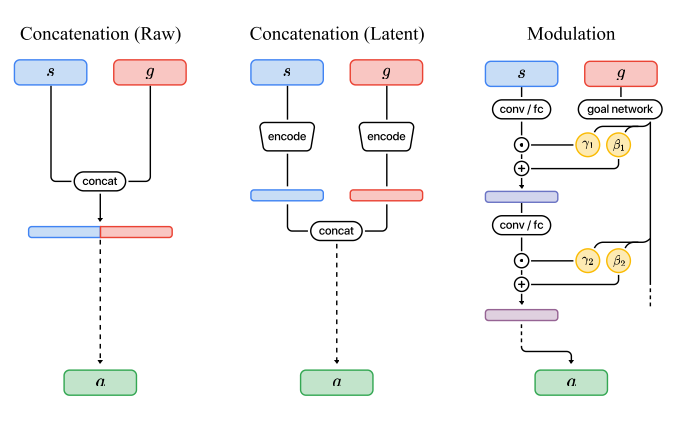

The authors’ suggestion is to effectively do multiplication instead of concatenation. They put the goal/query in to a goal network, which outputs two vectors \(\gamma_1\) and \(\beta_1\). At the same time, the state is put in to its own network, yielding some representation \(s_1\). The critical step is that, rather than directly adding these, they use \(\beta\) and \(\gamma\) as linear transformations, computing a new representation.

\[s_2 = (s_1 * \gamma_1) + \beta_1\]To this effect, the authors do a similar transformation at each layer, with different \(\gamma\) and \(\beta\) values.

Their model is the one titled 'modulated'

Experiments

The authors generate 4000 training programs that they train their model on. From this, they randomly sample environment states and ask the agent to solve the programs in the environment. These programs involve a number of tasks, such as crossing bridges, chopping wood, or finding resources.

The algorithm is then tested on 500 programs of equal length, and 500 programs with twice the length. The authors measure whether or not the program was able to complete the assigned task.

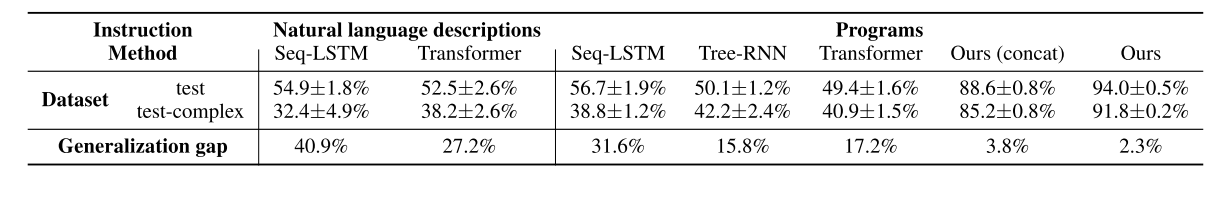

For baselines, the authors compare their model with several other models (see table) as well as some models which are given a natural language instruction instead of a program.

Annotators were used to generate natural-language versions of the instructions.

Their performance degrades on the longer tasks (marked 'test-complex') but not by much.

Overall, the argument for their model is pretty convincing.

It obtains the best results by a pretty convincing margin, with a minimal generalization gap between the train and test set.

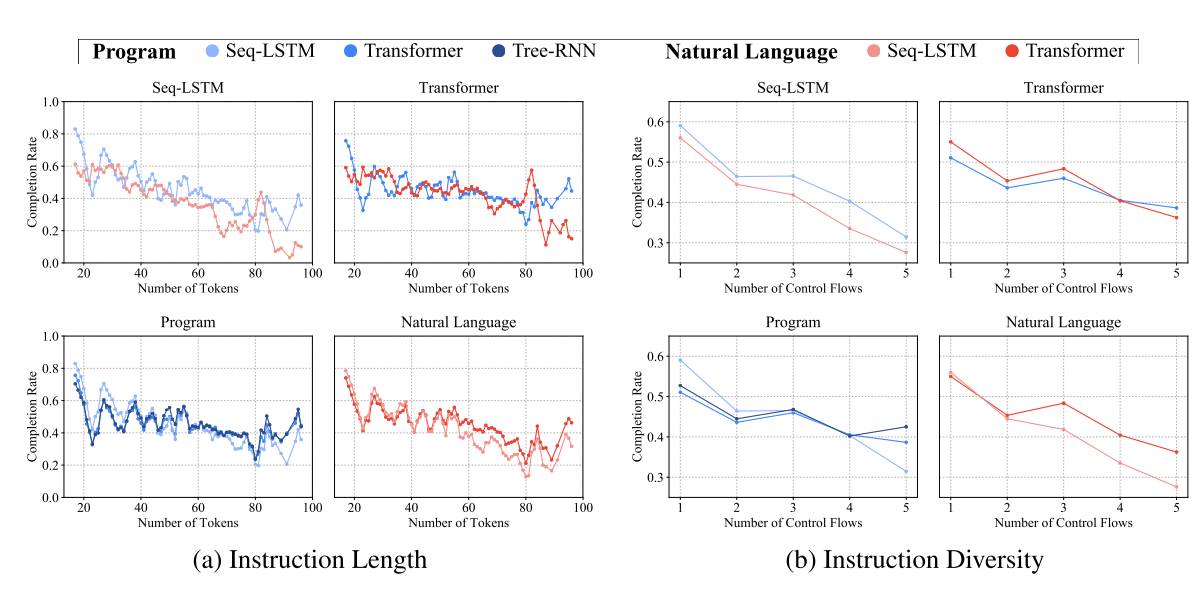

They also included studies showing how performance drops when the programs grow in length or a larger number of instructions are included.

The program-based models (blue) generally drop off less harshly than the natural-language based ones (red), but the difference isn't that sharp.

Future Directions and General Thoughts

To be honest, I feel like I’ve seen the majority of the content in this paper elsewhere. I won’t put too much weight on that fact, because I can’t name where I’ve seen it, but it does feel similar to other work, even if this specific model wasn’t used for program execution. Their results are fairly convincing, but I feel like that’s because they did a lot of the work themselves by writing the programs, and you still need to ‘program in’ each type of object. For instance, if you want the algorithm to learn to chop wood, you still need to define a reward function for chopping wood. That’s definitely simpler than solving the whole problem at once, but I’m not sure if the gains are that great.