Behavioral Suite for Reinforcement Learning

27 August 2020

Machine learning researchers have often lamented that it can be difficult to know exactly what your algorithm is struggling with. What’s more, because of the incentives involved in the publishing process, authors often (perhaps inadvertently) present their algorithms in the best light, making it hard to objectively compare multiple works. DeepMind has a new benchmark that might help ameliorate these problems.

Authors

- Ian Osband (Res. Sci. - DeepMind)

- Yotam Doron (DeepMind?)

- Matteo Hessel (Staff Res. Eng. - DeepMind)

- John Aslanides (Res.Eng. - DeepMind)

- Eren Sezener (Res. Eng. - DeepMind)

- Andre Saraiva (Res. Eng. - DeepMind)

- Katrina McKinney (Res. Program Spec. - DeepMind)

- Tor Lattimore (Res. Sci. - DeepMind)

- Csaba Szevepari (Prof. - UAlberta CIFAR AI Chair)

- Satinder Singh (Toyota Prof. - UMich)

- Benjamin Van Roy (EE Prof. - Stanford)

- Richard Sutton (Dist. Res. Sci. - DeepMind, Prof. - UAlberta)

- David Silver (Princip. Res. Sci. - DeepMind)

- Hado van Hasselt (Res. Sci. - DeepMind)

ArXiV: https://openreview.net/pdf?id=rygf-kSYwH

Background

While deep reinforcement learning has made major strides and attracted huge amounts of interest, it’s no secret that there are many unsolved problems. Speed of learning (data inefficiency) is probably the most commonly bemoaned issue, but what factors are slowing down speed of learning can be hard to diagnose. Major difficulties include learning long-term dependencies, credit assignment, ‘quick learning’ (e.g. don’t bump in to a wall twice), exploration, generalizability and … you get the idea, it’s a long list. This new framework from DeepMind is an open-source (yay!) way to benchmark and evaluate your agents on a variety of these issues.

Core Idea

DeepMind’s Behavioural Suite (BSuite) aims to provide clean, minimalist and isolated tests of a variety of aspects of reinforcement learning. It achieves this by giving tasks that involve some difficulty and giving the algorithm a finite amount of time to solve a task. This task can be scaled in difficulty, providing indication to how well various algorithms are able to handle that task. The authors say that their goal is to make their tasks targeted, simple, challenging, scalable and fast (they can presumably all be completed in 30 minutes!). These tasks can be divided into 7 groups as follows:

- Basic : This is intended to test, you guessed it, performance in traditional learning environments, like the bandits scenario

- Credit Assignment : The ability to figure out what factors are contributing to rewards in the presence of confounding variables

- Exploration : Exploring the environment effectively (usually helpful in solving sparse rewards)

- Generalization : The ability to succeed in scenarios different from how the agent was trained

- Memory : … how well the network does when it has to remember stuff

- Noise : Robustness to noisy rewards

- Scale : How well the algorithm is able to handle rewards of different scales

Details (lite)

There are a fair number of tests in the environment, so I’ll focus on the ones that the authors highlighted.

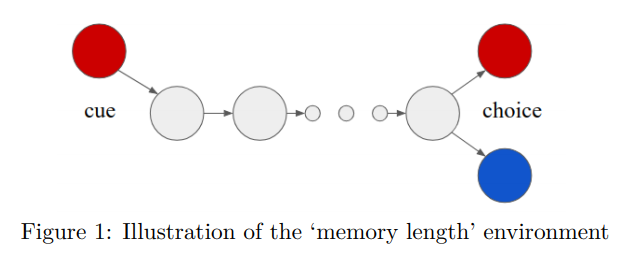

The first one is essentially the RL version of the bit-copying test that we’ve seen in RNN tests.

In these algorithms, the algorithm is provided with a cue during the first timestep.

After a number (N) of timesteps with no prompt the agent is required to make a choice, where the correct choice was basically given by the cue.

The algorithm receives rewards based on its choice, and the algorithms are given 10K episodes to learn the problem.

This is then repeated at various values of N, ranging from 1 to 100.

The agent’s score can then be compared to the optimal regret and random choice (I mean, you can compare it with whatever you want).

Shockingly, this task can be pretty difficult for a lot of algorithms. RNNs fail if you just give them enough time.

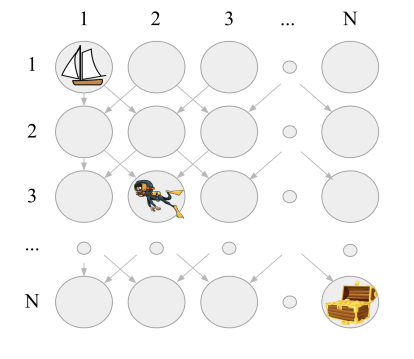

The second game is ‘Deep Sea’, which is intended to test deep exploration.

The agent is being lowered to the sea floor as represented by a one-hot grid.

The agent starts as far to the left as possible, and must move either left or right at each timestep (and always down).

Once the agent reaches the bottom of the sea floor, the episode ends without reward : unless the agent went all the way to the right, in which they get a hefty reward from the treasure chest.

The game is as wide as it is tall, so the agent only gets the treasure chest iff they go right at for each action.

Just to be special sadists, there’s another twist - each time you go right, there’s a slight negative reward, which can act as a deterrent for any agent that starts to go right.

The treasure chest is easily enough to offset the cost, but the agent doesn’t know this when they start exploring.

The last experiment I’ll cover (there are 15 total, although many are closely related) is the ‘Umbrella Length Problem’. In this, the agent is given a choice that matters early on (e.g. whether or not to bring an umbrella to work), a bunch of irrelevant choices, and, finally, a reward! The question is whether the agent can figure out what choices matter and which ones don’t.

Experiments

The authors test 3 different algorithms (well, 4, if you count ‘random actions’ as an algorithm). They use a basic DQN, a bootstrapped DQN and A2C - for some reason, A2C is the only algorithm equipped with any form of memory (it’s given an RNN).

I think that their plot of the scores is pretty attractive, so I”ll show it down below :

Turns out 'random' isn't that great of an algorithm...

Unsurprisingly, the only algorithm with memory (A2C) is the only one that does well on memory, while the only algorithm with an explicit memory mechanism (bootstrapped DQN) is the only one that does well on the exploration tasks.

One thing to note is that neither algorithm actually receives full score - for instance, A2C fails to remember the cue after being given just 30 timesteps.

Future Directions & General Thoughts

I actually see tremendous value in this work. I think that having a core test-suite is a great way for us to get a feel for what works and what doesn’t work in reinforcement learning. The authors comment that it can eventually help us build intuitions and data that can be used to build theories, all of which will bring us a little bit towards being a real hard science. Having benchmarks helps us identify whether we’re making real progress as a field, which is absolutely critical to the area’s sustained growth.

That being said, I don’t think this will become the ImageNet of RL (the authors pretty explicitly say that they don’t want it to be either). It’s meant to be used as a diagnostic, not as a score, which I think is a pretty level-headed approach.

That being said, I think my biggest concern is the thoroughness of these problems. For instance, the authors advertise that the deep sea problem is particularly hard because only one of the \(2^N\) possible sequences of actions leads to a big reward. While this is true, if you look at the problem in the terminal state spaces, one of \(N\) possible terminal states gives a reward, which is MUCH more tractable. Additionally, it can be reached by continually using just the same action, which is something that can happen pretty easily, as a network might have high bias that leads it to always choosing the same action, or the algorithm might have action-repeat turned on.

Similarly, it would be interesting to see more experiments in things like the umbrella example or the memory example: what if the intermediate confounding variables were actually useful for predicting causal dynamics, but ultimately these dynamics had no effect on the reward? Or, for exploration, what if you had a lottery ticket that usually punished you, but could pay off massively such that it had positive expected value (to be clear, lottery tickets DO NOT have positive expected value, don’t buy them). That’s honestly my biggest problem with the suite - I just wish there were more of it. The good news is that it’s open for open-source development, so hopefully we’ll see more great contributions soon. I personally fully intend on using the suite as a diagnostic and reporting my results where appropriate - that’s the highest praise I think I can give.