(NALU) : Neural Arithmetic Logic Units

30 August 2020

Neural Networks can’t do addition. Or subtraction. Or multiplication. Your first grader probably can. Let’s fix neural networks.

Authors

- Andrew Trask (Res. Sci. - DeepMind, PhD Cand. - Oxford)

- Felix Hill (Res. Sci. - DeepMind)

- Scott Reed (Sen. Res. Sci. - DeepMind)

- Jack Rae (Sen. Res. Sci. - DeepMind)

- Chris Dyer (Asst. Prof. - CLab, CMU)

- Phil Blunsom (Assoc. Prof. - Comp. Ling. Lab, Oxford)

ArXiV: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1808.00508.pdf

Background

Extrapolation has long been lauded as one of deep learning’s strengths, with many marvels such as deep double descent, where overparameterizing your model (stack more layers!) can actually lead to better results, despite everything that VC-theory tells you. In many ways, their results are impressive - I probably don’t need to remind you of their successes in image classification & generation, or NLP, or RL. However, these tasks typically involve testing the model on data that is drawn from the same distribution as the testing data (this is a little bit fuzzier in RL & generative tasks, but I digress.) When it comes to extrapolation, neural nets often perform very poorly.

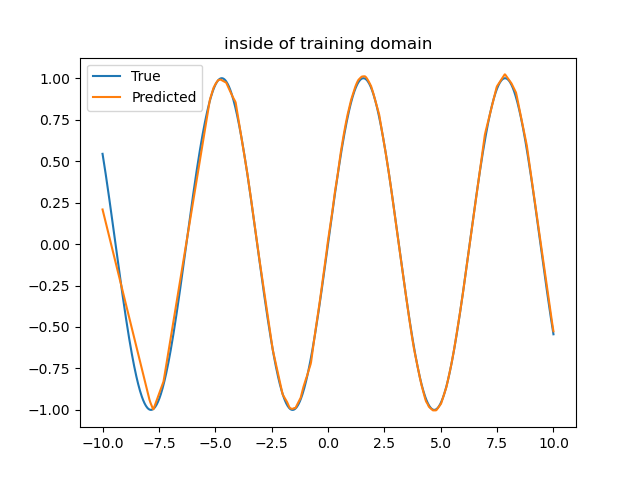

For instance, have you ever trained a neural network to learn the sine function? It can fit the data really well.

For instance, if we train the network to emulate the sine function on the range [-10, +10], it can learn to mimic it pretty well, as shown below.

They're virtually indistinguishable, so one obscures the other. But you can already see something weird happening on the left.

However, even though the periodic nature might be natural to a human observer, let’s take a look at what the function looks like if we zoom out and ask it what the sine function looks like on the range [-20, +20].

Play it live here! https://colab.research.google.com/drive/1a6ZOIMGcSj7bJV-CjQRQGj_J4jW90yPz?usp=sharing

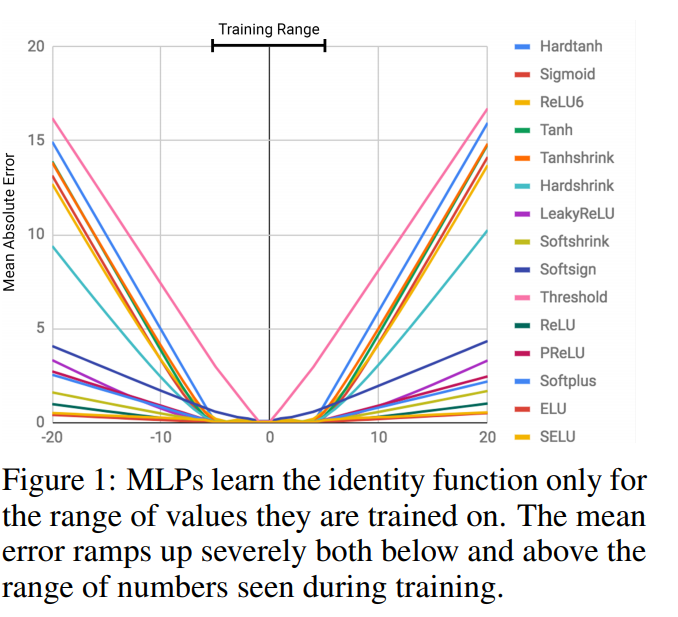

It turns out that pretty much all neural networks share problems similar to this, where they really struggle on extrapolation, even for extremely simple tasks.

This is true even of very simple tasks such as addition, subtraction, multiplication and division.

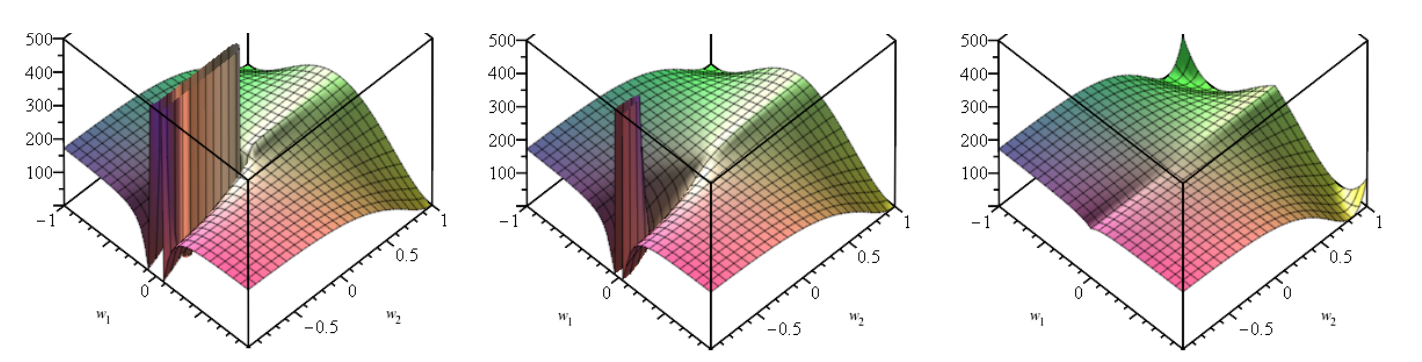

The authors of this paper plot the extrapolation error of an MLP trained to perform addition on inputs in the range [-5, +5] below.

Core Idea

This paper tries to provide a new layer that is pre-dispositioned to easily learn the four basic operations that we talked about above. Your initial reaction might be : aren’t each of those functions already differentiable? You might multiply the outputs of two layers all the time, which is true. However, there are many different combinations of items that might be multiplied (or added, or subtracted), and this paper is also concerned with learning that mapping.

The author’s new layer essentially consists of a weighted sum of an addition module and a multiplication module. The sum is weighted by some factor \(g \in (0, 1)\), such that the output of the layer is \(\vec{g}\vec{a} + (1-\vec{g})\vec{m}\) where \(a, m\) are the outputs of the addition and multiplication modules respectively. When \(g=0\), we only output the result of addition and when \(g=1\) we only output the results of multiplication. The authors draw an allegory to ALU’s (arithmetic logic units), which are one of the core units of a computer.

At a high level the addition layer (which the authors term the ‘neural accumulator’ (NAC)) is just a linear layer where the weights are dispositioned to be either \(\pm 1\) or \(0\). Similarly, the multiplication layer first takes the log of the inputs, multiplies the log-space inputs by the weights, and then takes the exponent. Because \(Wx\) results in a linear sum of the values in \(x\) and the \(exp\) function maps addition to multiplication, this is an intuitive way to transform the classic NN model to a multiplicative space.

The authors show that this makes networks better at counting, converting natural language to numbers and modelling environments.

Details

Addition/Subtraction

The equation for the addition module is \(\vec{a}=\hat{W}x\). This looks disarmingly normal - it’s a classical linear layer without bias. The special part is how \(\hat{W}\) is calculated.

\[\hat{W} = tanh(A) \cdot \sigma(B)\]where \(A, B\) are weight matrices and \(\sigma\) is the sigmoid function. Intuitively, most values of tanh map to something very close to -1 or 1, while most values of \(\sigma\) map very close to either \(0\) or \(1\). This means that, in theory, \(tanh(A)\) should easily converge to a matrix of \(\pm 1\) and \(\sigma(B)\) should be 1’s and 0’s. The elementwise multiplication of these two gives you a matrix with most values being one of \(-1, 0, 1\).

Each row in the output then results in summing all of the inputs with corresponding 1’s and subtracting all of the inputs with corresponding -1’s.

Multiplication/Division

Because linear layers are … linear, they’re very good at summing input values. One natural question might be how to teach them to multiply inputs. Because \(exp(a+b) = exp(a)exp(b)\), we can think of the expoential function as mapping addition in its inputs to multiplication in its outputs. Summing any number of values and then taking the exponent is the same as taking the exponent of each value first and then multiplying the results.

The authors leverage this with a layer in the form \(exp(Wx)\). However, this has the unfortunate after-effect that we’re now outputting something that grows exponentially with the inputs. To fix this problem, the authors first take the log of the inputs, yielding

\[\vec{m} = exp(W\log(\vec{x}+\epsilon))\]where \(\epsilon\) is added for numerical stability and \(W\) is not shared with the additive units.

Finally, the gating variable between the two (\(g\)) is just a linear function of the input.

Experiments

The authors have a good variety of tasks that they work on, although I will note that all would probably be considered to be in the range of toy domains.

The first experiment is to test whether or not the units are able to actually compute (and extrapolate on) the functions that they were designed to be used with.

In short, yes, they do very well (as shown below), although this is pretty unsurprising, given that these networks start with a very strong bias towards the correct results, so this is to be expected.

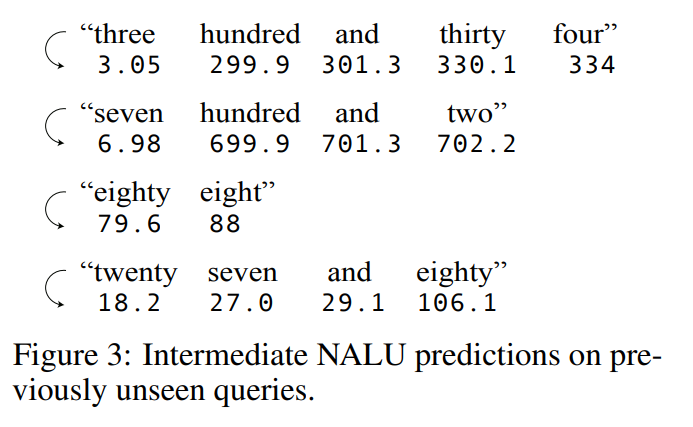

The authors also perform an experiment where the network has to parse natural language strings to integers.

For instance, given the string “seven hundred and seventy seven”, the network should output 777.

This is achieved by stacking NALU layers on top of LSTM layers and then feeding in tokens to the LSTM.

Intuitively, this seems like a good taks for the NALU, because when you read the phrase “seven hundred”, you should first store a 7 upon seeing “seven”, then multiply the stored value by 100 upon seeing the word “hundred.”

Reassuringly, the network performs well here as well, and creates coherent predictions even when given part of the string.

Finally, the authors give the network an RL task, where the agent must reach a goal after waiting for exactly \(T\) timesteps.

While their network performs similarly to the baseline during training, it really shines when you start asking it to generalize to values of \(T\) that it hasn’t seen before.

That being said, it does still fail after a disappointingly low value of \(T\) (around 20, after being trained on values of \(T\) from 5 to 12).

Future Directions & General Thoughts

I see a lot of value in this work, but I do think that it’s far from being a fully-studied area. At a high level, the authors are basically hand-engineering layers that default to learning these functions. There are still a number of important things that are left un-done here, including

- seeing how well these layers integrate with arbitrary systems

- many, many, more mathematical functions (e.g. periodic functions or exponentiation)

- learning new, generalizable mathematical functions Additionally, I’ve heard that these results are fairly hard to replicate, which gave rise to papers like this. On a fundamental level, I think we should be trying to solve the issues that make layers like this useful : what are the real lessons to be learned here? How could an ML model learn them on its own? And how could it learn when to apply different functions?

One other takeaway from this paper is their method of selectively construction weight matrices out of other weight matrices, as in their NAC. I think it provides a good template for introducing human biases in to the wieghts of networks in ways beyond just regularization. While I’m sure that this is not the first paper to toy with the idea (for that matter, you could say that ConvNets do a similar thing), it’s the first time I’ve seen it phrased this way, and it’s quite exciting to me. I can already think of several ways that it might be learned, ranging from reframing the residual connections in ResNets to using them for meta-learning.