Large-Scale Study of Curiosity-Driven Learning

01 September 2020

Curiosity, or intrinsic exploratory motivation, has been one of the hot-topics in RL recently. This paper finds that an agent motivated by curiosity alone performs well on a large variety of tasks, which raises questions regarding the fundamental natures of the environments.

Authors

- Yuri Burda (Researcher - OpenAI)

- Harri Edwards (Res. Sci. - OpenAI)

- Deepak Pathak (Asst. Prof. - CMU)

- Amos Storkey (Prof. - UEdinburgh)

- Trevor Darrel (Prof. - BAIR, Berkeley)

- Alexei A. Efros (Prof. - BAIR, Berkeley)

ArXiV: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1808.04355.pdf

Background & Core Idea

The paper Curiosity-Driven Exporation by Self-Supervised Prediction was one of the first papers to cause excitement about curiosity as a mode for efficient exploration. This model of curiosity-driven learning provides extrinsic reward for taking actions that the agent isn’t able to model well. The intuition is that the actions (and corresponding states) are more likely to be different from the rest of the state space that the agent has explored thus far. This should lead to it exploring more interesting behaviours.

When we think of rewards in reinforcement learning, we typically think of extrinsic rewards, which are defined by the environment. However, it’s also possible to create intrinsic rewards, which can be thought of as rewards that the agent gives itself (although it does NOT have direct control over these rewards). For a human analogy, you could say that the only real reward in human life is reproduction, but reproduction is probably very far from the primary source of happiness in your life. Your body gives you positive signals for doing things that generally increase your fitness and security, and these can be thought of as extrinsic rewards. These can be very useful in guiding you to long-term useful behaviours.

However, it’s interesting to ask what would happen if an agent were driven only by its intrinsic curiosity. The authors study how well such a model can perform.

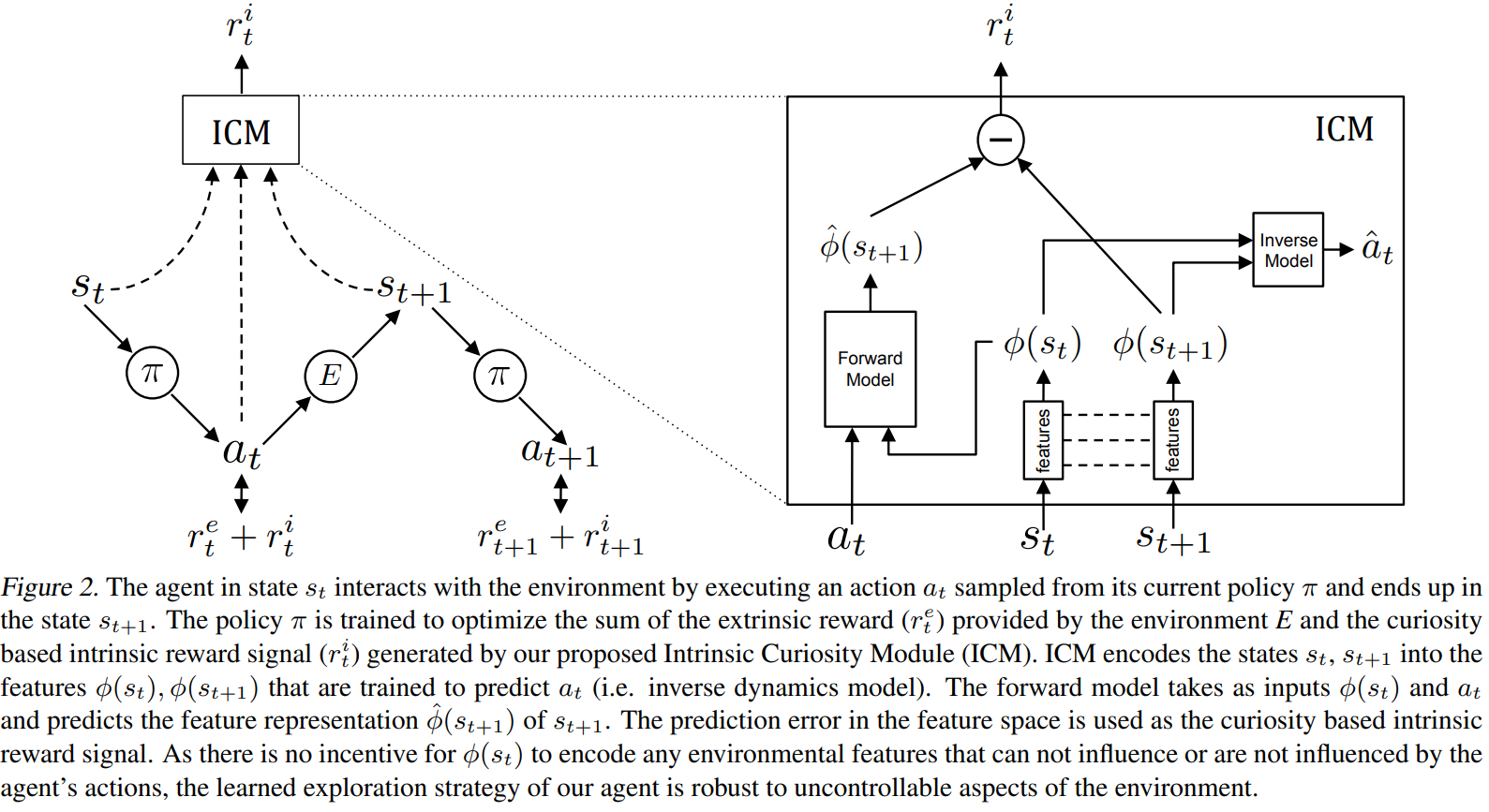

In this case, the intrinsic reward is given by an intrinsic curiosity module (ICM).

For refreshers, a diagram of the module is shown below, but if you haven’t read the paper, it’s likely useful to read it here first.

Details & Experiments

Of note, the agents work in a modified environment where death is not the end, so the agent’s environment reset. This results in them being put in a place that they’ve already seen, which they are undoubtedly not very ‘curious’ about.

The authors test the algorithm in 54 environments: 48 atari games, Mario Bros, 2 Roboschool scenarios, two player pong, and 2 mazes. Of interest, one of the mazes has a TV that is controlled by the agent. TVs like these are often a problem for curious agents, as it can be hard to predict what the TV does (leading to high curiosity), but the TVs are ultimately meaningless in the greater scope of the task.

In each environment, the agent (and the curiosity module) operate on a learned feature space. The authors investigate 4 different possibilities for the feature space:

- Raw Pixels: The learned feature space is the identity function

- Random Features: A randomly-initialized CNN is used for encoding

- Inverse Dynamics : This is the feature embedding that is used in the ICM above.

- VAE Features: A VAE is used to compress the features to a small latent space.

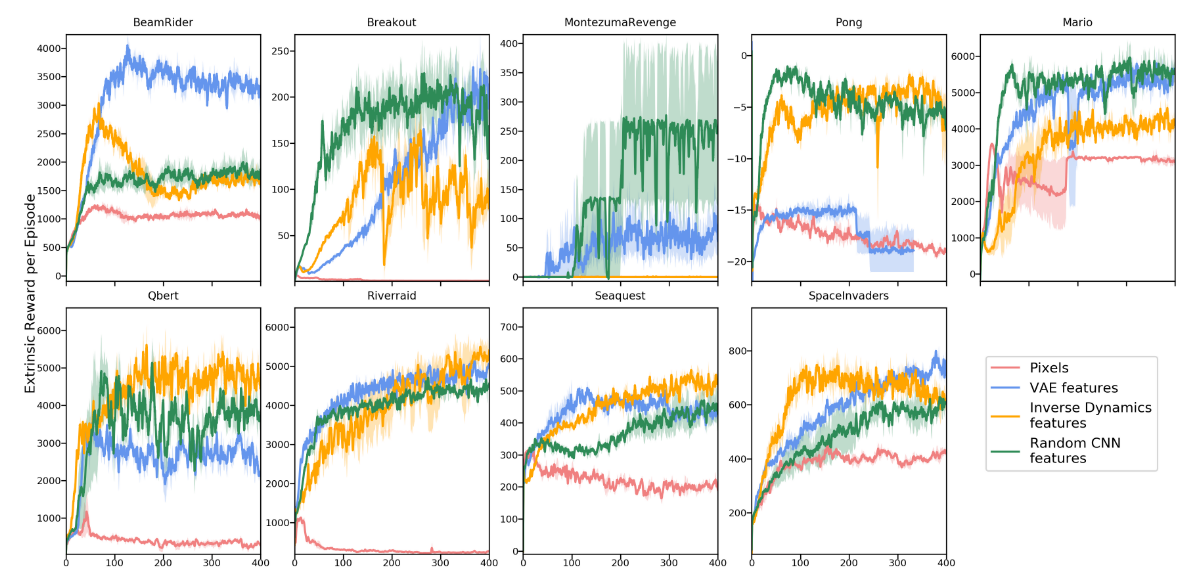

Shockingly, they great pretty good results, as shown below.

The first thing they note is that, despite seeing no real extrinsic reward signal, most of these curves go up.

This means that, by fulfilling their curiosity, the agents also happen to be fulfilling the goals of the game, which they have no idea about.

In 2-player pong, the agents even learn to rally successfully.

The authors (rightly) note that this may just be because of good game design - games should encourage you to do interesting things in order to win them.

By that logic, assuming that the version of ‘curiosity’ learned by the ICM module aligns closely with human curiosity, then the game can be reasonably expected to give high rewards for things that the agent is curious about.

The second interesting result is the random features encoding is actually really solid. On several games, it actually performs the best. The authors hypothesize that this may be because the encoding is stable and low-dimensional, but it does raise real questions.

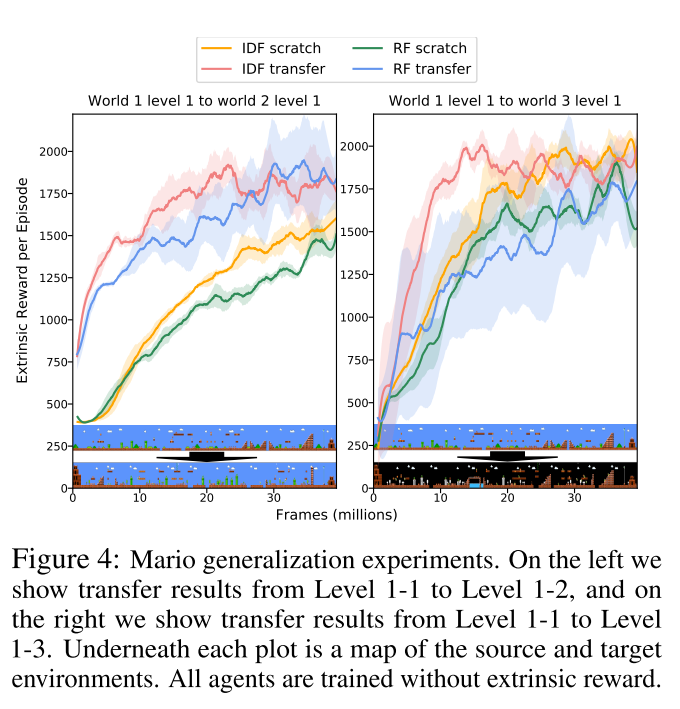

The authors also test how well agents trained on one level of Mario are able to transfer to other levels.

Interestingly, the simple change in background significantly hampers the curious model's ability to transfer.

Transferring does appear to help, which is encouraging.

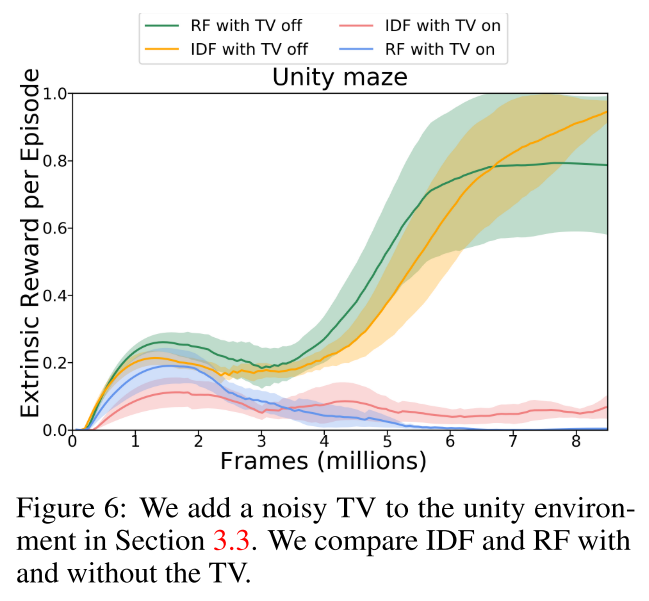

Finally, the authors show that they are able to perform very well in the maze environment, well outperforming the models that use the actual extrinsic reward (the extrinsic model gets no reward).

That being said, turning the TV on does ruin the performance of the curious agents.

So, that problem is still unsolved. (RF corresponds to random features, ICF to the ICM features.)

Future Directions & General Thoughts

This paper has a feeling similar to the neural evolution paper by Uber, where the authors showed that random search performs similarly to gradient descent. It’s very encouraging that intrinsic rewards can allow the agents to perform well, although the authors do not provide baselines with extrinisc rewards for comparison. One could imagine that some combination of curiosity and empowerment could actually learn to create algorithms that only need a little fine-tuning to perform very well.

Additionally, the fact that the various models work marginally better than the learned representations raises in to question how useful the representations that networks have learned in other domains are. If we aren’t doing much better than random, what progress are we really making? Or, alternately, is it the case that the we’ve learned to initialize networks in ways that often bias them to be close to useful representations? I’m excited to see if there is substantially more work that takes place in this area.