What is being transferred in transfer learning?

10 September 2020

The title says it all. Ever wondered what tangible benefits your network is getting from transfer learning? This paper analyzes a ResNet-50 that is initially trained on ImageNet but subsequently fine-tuned for various permutations of the DomainNet and CheXpert datasets.

Authors

- Behnam Neyshabur (Sen. Res. Sci. - Google)

- Hanie Sedghi (Sen. Res. Sci. - Google)

- Chiyuan Zhang (Res. Sci. - Google)

ArXiV: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2008.11687.pdf

Background

Transfer learning is a common practice in deep learning. In the simplest case, you might have a task that you want a model to learn, but you don’t have much data for it. However, you have a similar task with substantially more data available. You hypothesize that some of the ‘skills’ (using the term very loosely) that are useful in solving the latter task might also be applicable to the former. You can attempt to transfer the skills from the second dataset to the first by initially training your model on the second, larger dataset, then fine-tuning on the dataset you actually care about. The alternative is to simply randomly initialize your model and attempt to train directly on the target dataset, which may prove difficult. As a result, transfer learning has becomes a staple in both NLP and CV tasks, as well as many, many others.

This process can often improve your final performance on the smaller task that you are working on. However, like much of deep learning, the process is in many ways a black box.

Core Idea

This paper attempts to illuminate the subject a little by providing a number of experiments. Each experiment is designed to answer a question, as follows:

1. How much of the knowledge transfer is accounted for by feature reuse?

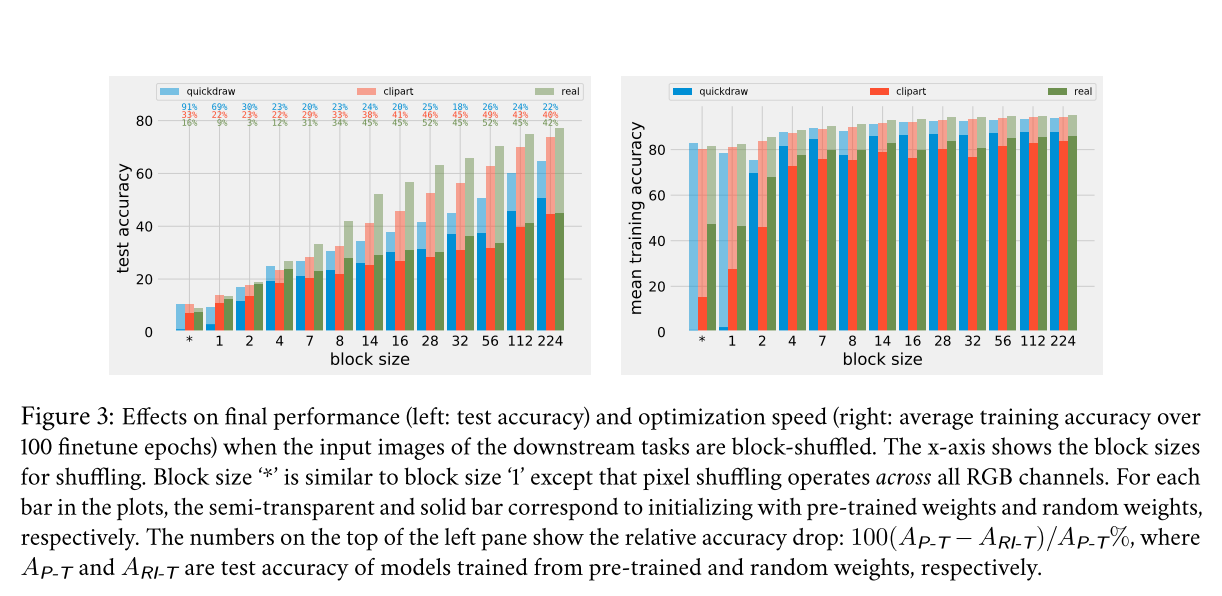

Feature re-use relies on the concept that certain features that are derivable from one dataset can also be combined to perform useful representations on another dataset. The authors investigate how important this property is by designing datasets where the features learned on ImageNet are no longer reusable. This is achieved by dividing the images in to blocks and then shuffling these blocks for each photo (it’s unclear if all images undergo the exact same permutation). This destroys the spatial structure of the original images, and therefore renders the spatially defined features (which make up most of the lower layers of a CNN) useless. The authors find that, even when all of the spatial structure is destroyed, the transferred model still outperforms the randomly initialized one, indicating that it is learning something else as well. The authors surmise that these may be low-level statistics about the data, although there isn’t any work to formalize this intuition.

2. Investigating mistakes

The authors discover that pretrained models tend to make the same mistakes as other pretrained models when it comes to classification. The same is not true of randomly initialized models, which make a variety of mistakes. However, the authors note that the errors of the pretrained models seem qualitatively more ‘understandable’ - they tend to make mistakes on classifications where humans also struggle, whereas the randomly initialized models make errors on both easy and difficult examples.

3. Representaton Similarity

The authors use centered kernel alignment (CKA) to measure the similarity between features learned by the pretrained versus randomly initialized models. Unsurprisingly, the pretrained models tend to learn similar feature representations, while the same cannot be said of the randomly initialized ones.

4. Parameterization Similarity

The authors also measure the \(l_2\) norm between the parameters of different pretrained and randomly initialized models. I’m sure you can guess the results - the pretrained models all have parameters that are quite close in the \(l_2\) space, while the randomly initialized ones are more spread out.

5. Performance Barriers & Loss Basins

The authors find that the pretrained models typically end up in the same loss basin after fine-tuning. They formalize the idea of a loss basin with the following three principles:

- The variance of the loss within the basin is low

- Adding Guassian noise to the points within results in higher loss because it pushes the points out of the basin

- The loss of the points near the basin is higher than those in the basin

I’m sure I don’t need to say it, but the randomly-initialized models don’t usually end up in the same loss-basin.

6. Module criticality

Module criticality is the notion that some modules are more sensitive to feature perturbations than others. This sensitivity is measured by observing how much a perturbation to the weights of that layer cause an increase in loss. Aligned with existing literature, the authors find that lower modules (e.g. the initial convolutions) are less critical than higher level ones. The authors also find that there is a point in training of the randomly initialized network where its modules rapidbly become much more sensitive.

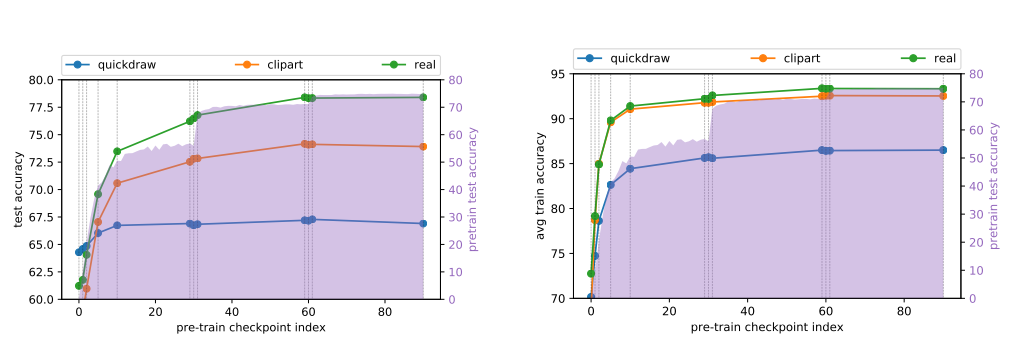

7. Which pretrained checkpoints are best?

It’s possible to stop the pretraining process at any checkpoint and begin finetuning that version of the model.

Intuitively, one could assume that the later stages of pretraining might involve learning features that are more specific to the pretraining dataset, and therefore might not transfer as well.

The authors’ results somewhat confirm this intuition.

They find that it is better to use later checkpoints, but only marginally so.

During pretraining, they note that during some epochs, the network makes sudden improvements on the pretraining task.

These, unfortunately, don’t correlate to sudden improvements on the downstream task, as shown below.

What actually causes these sudden improvements is still an open problem.

Details & Experiments

Training Details

For all tasks, a ResNet-50 model is trained on ImageNet. It’s not clear whether or not the exact same instance of the model is used as the basis for all of the pretrained models, but it looks like it is.

Feature Reuse Experiments

The authors experiment with DomainNet & CheXpert as downstream tasks.

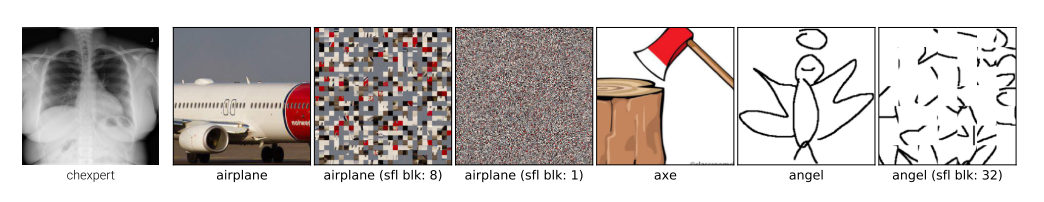

DomainNet consists of 3 different domains: quickdraw (crappy MsPaint-style artwork, shown above), clipart (you know what this is) and real images.

The authors experiment by dividing the images in to blocks of different sizes, and shuffling the blocks (examples shown above).

Each image is of size 224 x 224, so a block size of 224 amounts to no shuffling at all.

As you can see below, decreaseing the block size does generally decrease the percentage improvement yielded by transfer learning, but it does not eliminate it.